Monika Winiarczyk

The Equivocal Woman: Shifting Perceptions of Synagoga

4 February 2013

http://beyondborders-medievalblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-equivocal-woman-shifting.html

Synagoga and Ecclesia first appeared in the ninth century in Northern France and Southern Germany, where they were intended as representations of the Old and New Testament and personifications of Judaism and Christianity, respectively. Through their depiction in carved ivory panels, to stained glass windows and manuscript illuminations, the figures developed a distinct iconographical tradition, which featured prominently in the pictorial arts, contemporary drama as well as in Christian theology, appearing in commentaries, exegesis, and sermons.[i] For example, Ecclesia and Synagoga were the main actors in Pseudo-Augustine’s sixth century Sermo Contra Paganos, Judaeos et Arianos, (Sermon Against Pagans, Jews and Heretics) as well as central figures in the twelfth- century exegetical sermons of the French abbot, Bernard of Clairvaux.[ii] The ubiquitous presence of the figures in medieval art and literature makes it almost impossible to engage in medieval studies without coming across Synagoga and her Christian counterpart.[iii]

Any discussion of the figures must begin with a description of Synagoga and Ecclesia’s traditional iconography. In order to do so, it is perhaps best to turn to, what is acknowledged as one of the most celebrated examples of the motif; the south facade of Strasbourg Cathedral.[iv]

On the right of the facade is the regal Ecclesia. Adopting a powerful stance, her legs are set wide apart as she throws her shoulders back in an upright posture. The heavy drapery of her robe gathers in orderly folds at her feet and she is the image of might and stability. Every movement of her body appears decisive and controlled as she tightly grips a cross in her hand. A crown sits firmly on top of her head and identifies Ecclesia as a ruling Queen. No aspect of Ecclesia’s appearance communicates inertia, uncertainty or any other weakness. Her power and strength are absolute.

Standing across from Ecclesia, to the left of Solomon, is the figure of Synagoga. Although her beauty matches that of Ecclesia, unlike her counterpart Synagoga is the image of weakness and defencelessness. Her stance is weak and she is hunched over. Her movements seem uncertain and she appears to be slipping out of the design, with her elbows protruding beyond the facade. The drapery of her robe falls in a muddled pile at her feet, giving the impression that she may trip over it. Her frailty is further emphasised by the blindfold tightly wrapped around her eyes which represents the Jews inability to see Christ as their true Messiah. In her hand she holds the tablets of the law which are slipping from her grasp and tangled up within the holds of her robe; symbolising the Jewish attachment to the now obsolete Old Law. Like the broken staff in her hand, Synagoga looks damaged and defeated. She is isolated and turns away from the rest of the facade. Her only symbol of power was a crown, which is no longer visible, located at her feet. It suggests Synagoga is the overthrown Queen who was once powerful but whose time has now passed.[v]

Together, Synagoga and Ecclesia represent the contrast of defeat and victory; of subordination and power and of despair and hope.[vi] This opposition of conquered and conqueror was a defining feature of the motif from the eleventh century onwards and creates a powerfully dramatic but also highly enigmatic image which begs further investigation.

In light of her omnipresence and striking appearance, it is not surprising that since the late nineteenth century Synagoga’s flimsy beauty has inspired a wealth of literature and numerous interpretations.[vii] One of the earliest studies of Synagoga was carried out in 1894 by Paul Weber. His fundamental text Geistliches Schauspiel und kirchliche Kunst (Religious Drama and Church Art) studied the relationship between pictorial representations of Synagoga and her depiction in medieval drama.[viii] Weber’s study viewed the figure as the embodiment of medieval anti-Semitism. He concluded that despite the figure’s beautiful appearance, like the deformed male Jew of Christian art, Synagoga condemned medieval Jews. Therefore initially the figure was seen as a further manifestation of Christian anti-Semitism, reflecting the writings of the Church Fathers, such as John Chrysostom, who condemned the Jews and accused them of immorality and madness.[ix]

This negative interpretation of Synagoga was questioned by Wolfgang Seiferth. His text, Synagogue and Church in the Middle Ages: Two Symbols in Art and Literature, reached a more ambiguous conclusion.[x] Studying the development of the iconography of Synagoga, from the ninth through to the fifteenth century, he concluded that due to the allegorical nature of the figure it denies any concrete definition. Seiferth traced the use of the female allegories or personification to Classical Antiquity when female allegories would often be used within a historical context to represent ideas which they did not literally represent.[xi] Using the example of the two female personifications of conquered lands depicted on the armour of the statue of Augustus at Prima Porta, Seiferth shows how multifaceted an allegory could be. Building of the argument that the meaning of the personification is volatile and strictly dependant on the context in which they appear, Seiferth concluded that when removed from the initial context the female personification could stand for anything.

This interpretation draws from the classical understanding of the function of the personification as presented by Morton Bloomfield, who stated that the connotations of a personification are not determined by what it represents but the predicates that are attached to it.[xii] As such Seiferth presents Synagoga as a far more complex figure which reflected the dual nature of Judaism in medieval Christian theology.[xiii] While the Jews were accused of deicide and condemned they were also acknowledged as God’s first chosen people. This can be seen in the writings of the French abbot Bernard of Clairvaux who adopting the fourth century ideology of St Augustine stated, ‘slay them not least my people forget.’[xiv] He believed that Jews should be protected as they are living relics of the Old Testament, and their conversion is a condition of the second coming of Christ. Thus he presented the Jews as playing a vital role in the past and future of Christian salvation history.

For Seiferth, Synagoga’s allegorical nature could accommodate the various incarnation of the Jew in Christian theology. Therefore rather than interpret the figure as a positive or negative representation of Judaism, he believed that the connotations of the figure were directly related to the specific circumstances of her representation. A similar conclusion was reached by Bernhard Blumenkranz who believed that Synagoga could both condemn the Jews and communicate their position within Christianity and Christian salvation history. However, Blumenkranz believed that the downtrodden appearance of Synagoga, contrasted against the victorious Ecclesia always communicated a sense of subordination and while the figure may not have been a negative representation, it did present Judaism as inferior to Christianity.

Ruth Mellinkoff’s study of medieval iconography supported this conclusion stating that the figures had a firmly established iconographical tradition which was intended on communicating the superiority of Christianity over Judaism. Synagoga’s traditional attributes of a blindfold, slipping tablets of the law and a broken banner all communicate weakness which was emphasised by the contrast with Ecclesia who’s attributes of a crown and upturned chalice are indicative of power.[xv]

These early studies focused on Synagoga and Ecclesia’s iconography in light of the Christian theological conception of the Jews; a conception which at times appears almost schizophrenic. While failing to agree on whether Synagoga was a flattering of damning representation of Judaism, all of these studies concluded that despite her beauty, Synagoga’s dissolute and defeated appearance communicated the secondary role attributed to Judaism in Christian theology.

What these early studies have provided is a solid foundation for the examination of Synagoga. However, there is a limit to how much can be achieved through iconographical analysis which is only examined in relation to Christian theology. Although these studies are a logical starting point, this approach fails to acknowledge Synagoga’s prominence and also the complexity of medieval Jewish-Christian relations. In medieval Christian Europe “the Jew” was not a mystical creature only featured in theology; the Jewish community played a significant role in medieval society and like their Christian counterpart was influenced and shaped by social and political change. Simultaneously, Synagoga was not limited to theological contexts and clerical audiences. Featured on public spaces such as cathedral facades, which would have been visible to Christians and Jews alike, it is necessary to consider the possibility that the figures could have functioned out with the context of Christian theology.

More recent scholarship has begun to take these wider considerations into account. Accepting the complexity of Synagoga’s iconography and the context in which she was displayed, scholars such as Sara Lipton and Nina Rowe are beginning to consider Synagoga’s multifarious nature [once again].

Notes

[i] Wolfgang S. Seiferth, Synagogue and Church in the Middle Ages: Two Symbols in Art and Literature, trans. by Lee Chadeayne and Paul Gottwald (New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1970), p.108; for example of drama see: John Wright, trans., Play of Antichrist (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1967).

[ii] St Augustine, Sermo contra judaeos, paganos, et Arianos de Symbolo, Migne, P.L. XLII, 1117-30 and Bernard of Clairvaux, ‘Sermones Super Cantica Canticorum’ 14.2.4 in Opera, ed. by Jean Leclercq et al. (Rome, 1957-77); Migne Patrologia Latina 42, 1115-1139.

[iii] Nina Rowe, ‘Rethinking Ecclesia and Synagoga in the thirteenth century,’ Hourihane, Colum, (ed.), Gothic Art & Thought in the Later Medieval Period: Essays in Honour of Willibald Sauerlander, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011) p.265

[iv] Nina Rowe, ‘Idealization and Subjection at the south Façade of Strasbourg Cathedral’ in Beyond the Yellow Badge: Anti-Judaism and Anti-Semitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture, ed. by Mitchell B. Merback (Leiden: Brill, 2008), p.179 and footnote 13 for list of example of Synagoga’s appearances on Cathedrals.

[v] This crown is no longer visible but the image shows a sixteenth century engraving which shows that originally there was a crown located at Synagoga’s feet.

[vi] Nina Rowe 2008 p.179 and footnote 13 for list of example of Synagoga’s appearances on Cathedrals.

[vii] See: Rowe 2008; Seiferth 1970; Nina Rowe, The Jew, the Cathedral and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Bernd Nicolai, ‘Orders in Stone: Social Reality and Artistic Approach. The Case of the Strasbourg South Portal,’ Gesta, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2002), p. 111-128; Otto Von Simson, ‘Le Programme Sculptural du Transept Meridonal de la Cathedrale de Strasbourg,’ Bulletin de la Societe des Amis de la Cathedrale de Strasbourg, Vol. 10, 1972, p.33-50 and Adolf Weis, ‘Die “Synagoge” am Südquerhaus zu Straßburg,’ Das Münster, Nr. 1 (1947), p.65-80; Ruth Mellinkoff, Outcasts: signs of otherness in northern European art of the late Middle Ages (Oxford : University of California Press, 1993); Annette Weber, ‘Glaube und Wissen-Ecclesia et Synagoga,’ in Wissenspopularisierung: Konzepte der Wissensverbreitung im Wandel, ed. by Carsten Kretschmann (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2003); Herbert Jochum, Ecclesia und Synagoga: Das Judentum in der Christlichen Kunst: Austellungskatalog (Saarbrücken: Museum, 1993); Cohen, E., ‘The Controversy Between Church and Synagoga in some of Bosch’s Paintings,’ Studia Rosenthaliana, Vol.18 (1984), p.1-11; Bernhard Blumenkranz, ‘Geographie historique d’un theme de l’iconographic religieuse: Les Representations de Synagoga en France,’ in Melanges offerts a Rene Crozet, ed. by P. Gallais and Y.J. Rious, 2 vols. (Poiteres: Societe d’Etudes Medievales, 1966), II, p. 1142-57; for discussion of Jews in medieval theology see Jeremy Cohen, Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity (London: University of California Press, 1999), for example p.134.

[viii] Paul Weber, Geistliches Schauspiel und kirchliche Kunst in ihrem Verhaltnis erlautert an einer Ikonographie der Kirche und Synagogue: Eine kunsthistorische Studie(Stuttgart; Ebner & Seubert, 1894)

[ix] John Chrysostom, Logoi kata Ioudaion I.6, Patrologia Graeca 48:852

[x] See: Seiferth 1970

[xi] James J. Paxson, ‘Personification's Gender,’ Rhetorica, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring, 1998), p.153.

[xii] Morton W. Bloomfield, ‘A Grammatical Approach to Personification Allegory,’ Modern Philology, Vol. 60, No. 3 (Feb., 1963), p.165.

[xiii] For discussion of Jews in medieval theology see Jeremy Cohen, Living Letters of the Law: Ideas of the Jew in Medieval Christianity (London: University of California Press, 1999)

[xiv] Robert Chazan, The Jews of Medieval Western Christendom, 1000-1500 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) p.37

[xv] Mellinkoff, Ruth, Outcasts: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages, vol. 1 (Oxford : University of California Press, 1993), p.49.

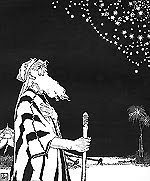

Moritz von Schwind, Sabina von Steinbach, 1844

Moritz von Schwind, Sabina von Steinbach, 1844

Monika Winiarczyk

She Moves in Mysterious Ways: Re-interpreting Synagoga

18 February 2013

http://beyondborders-medievalblog.blogspot.com/2013/02/she-moves-in-mysterious-ways-re.html

Reviewing the landscape of Synagoga’s historiography one can see that all these studies have interpreted the figure in relation to medieval theology. However theological interpretations of the subject would only be accessible to educated audiences who had enough of an understanding of contemporary theology to be able to apply them to the beautiful downtrodden figure of Synagoga.

Taking into consideration the allegorical nature of the figure and the notion that not all medieval spectators would look upon Synagoga as an abstraction of complex theological ideas, since the middle of the twentieth century, scholars have began to consider how specific contexts could have influenced Synagoga's reception. Most of these studies have centred on the depiction of Synagoga on the south facade of Strasbourg Cathedral.

The earliest of these studies were carried out by Adolf Weiss, Adalbert Erler and Otto von Simson.[i] All three of their studies identified the square in front of the facade as the seat of local justice and the site of the local municipal courts. Taking into account this legal context, all three come to the conclusion that the eschatological theme and heavenly judgement depicted on the south facade, would be seen by medieval audiences as a reflection of the earthly judgement of medieval legal practices.[ii]

Within this interpretation the victorious Ecclesia and defeated Synagoga, represent the innocent and the guilty parties of the medieval courts. While their presence in the eschatological iconography of the facade can be interpreted as a depiction of the saved and the damned; the innocent and the guilty parties in God’s final judgement.[iii] This conclusion was confirmed by Bernard Nicolai in his 2002 article, Orders in Stone: Social Reality and Artistic Approach: The Case of the Strasbourg South Portal.[iv] Considering the context in which the Strasbourg facade would have been seen, these studies concluded that within the right context Synagoga and Ecclesia could surpass their traditional roles as the personifications of Judaism and Christianity and depict the two spectrums of Christian morality; the sinful and the righteous; the damned and the saved; the guilty and the innocent.

Although these studies were the first to consider Synagoga as more than a representation of the Christian theological conception of Judaism, they still limited Synagoga to the realm of Christian theology by interpreting her representation within the context of Christian salvation history and the Christian understanding of morality. However two recent studies have gone beyond this theological reading. The first of these was carried out by Sara Lipton.[v] In her article, The Temple is My Body: Gender, Carnality, And Synagoga in the Bible Moralisée, Sara Lipton presented a new reading of the figure of Synagoga.

As the personification of the worldly and flesh oriented Old (Jewish) Law, Lipton presents Synagoga as a representation of the material world and examines the connotations communicated by her figure in the thirteenth century, Bible Moralisée which were illustrated Bibles, accompanied by an illustrated commentary.[vi] These Bibles took the form of a novel in order to present sacred texts and were aimed at a courtly audience.[vii] Instead of examining Synagoga in terms of her opposition with Ecclesia, Lipton examines the figure in relation to the medieval rhetoric of gender and through Synagoga’s relationship with male figures in the manuscript. In the commentary to several biblical passages Synagoga takes on various female stereotypes such as the Disobedient Wife; the Seductress ; the mourning Mother and the naive Daughter and the resentful sister. Depending on which of these roles Synagoga embodied, the figure altered from virtuous to sinful; from feminine to masculine to androgynous; from threatening to submissive and was transformed back again.

From this analysis the article comes to the conclusion that Synagoga as a representation of the material does not condemn the body or earthly world but rather reinforces its importance and value. This study re-evaluates the previously held belief that the Middle Ages viewed the material and spiritual world as binary opposites with the former being seen as bad and the later as good. A conclusion Lipton illustrates by considering Synagoga's fate throughout the numerous commentaries.

Nowhere in the commentary or accompanying text is Synagoga condemned or permanently ostracised. She is punished, buried, purged but ultimately redeemed. Synagoga and her corporeal nature are presented not as an antithesis to Christianity but as an integral part of the Christian identity; like women are an essential component of society. Sara Lipton believes that this conclusion is partially dictated by the nature of the Bible Moralisée and its intended audience. As luxurious material goods which were intended to be enjoyed for their material qualities, the Bible Moralisée in which Synagoga appears, praises the physical wealth which formed an integral and growing part of courtly life. Focusing on Synagoga’s femininity Lipton presents the argument that Synagoga’s female body can, in specific circumstances, be a representation of the complex relationship between Christianity and material wealth.

Synagoga’s female body was also the focus of Nina Rowe’s recent studies. Began in a 2008 paper, Idealization and Subjection at the south Façade of Strasbourg Cathedral, and expanded upon in her book The Jew, the Cathedral and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century, Rowe focuses on the appearance on Synagoga on cathedral facades, across central Europe, in the thirteenth century.[viii] Examining the opposition of the weak and beautiful Synagoga against the victorious and mighty Ecclesia, Rowe related the figure to contemporary politics and the social status of medieval Jews. She believes that the figures appearance communicated the imperial position towards the Jews. Under royal decree Jews were protected as their economic activity was vital to the wealth of the kingdom. However, Jews were also considered to be royal property. Attacking a Jew was viewed as a similar offence to attacking the King’s horse. Taking this into consideration, Rowe interprets the Strasbourg, Bamberg and Reims Cathedral facades in relation to the position held by the Jewish community within these cities and concludes that Synagoga communicated the ideal identity and social position of the Jew in thirteenth century Christian Europe:

"she is a servile yet integral member of the Christian milieu. Her beauty marks her as an insider within the ideal Christian system. Her decrepitude ensures her submission...she conveys the virtue of a Judaism that maintains a docile presence within the Christian domain."[ix]

This study does not present Synagoga as a representation of the theological Jew but rather the medieval Jew; the Jew who would cross the town square, under Ecclesia’s watchful gaze and nod a greeting to his Christian neighbour. Like Lipton related Synagoga to medieval attitudes towards the material world, Rowe interprets the figure in relation to the social position of the Jews in the thirteenth century.

These two studies can be viewed as an indication of the future historiography surrounding Synagoga. Having considered Synagoga’s relationship to Christian theology, scholars are now beginning to examine the figure in relation to the culture which created her. As Rowe stated, “Synagoga is an abstraction,” a creation of the medieval culture.[x] Consequently, she needs to be examined within the context of medieval Christian Europe and with respect to the contemporary understanding and conception of Judaism and the Jewish community or even beyond the boundaries of Judaism.

Notes

[i] See: Otto Von Simson, ‘Le Programme Sculptural du Transept Meridonal de la Cathedrale de Strasbourg,’ Bulletin de la Societe des Amis de la Cathedrale de Strasbourg, Vol. 10 (1972), pp.33-50; Adolf Weis, ‘Die 'Synagoge' am Südquerhaus zu Straßburg,’ Das Münster, Nr. 1 (1947), pp. 65-80; Erler, Adalbert, Das Strassburger Münster im Rechtsleben des Mittelalters (Frankfurt: V. Klostermann, 1954)

[ii] Bernd Nicolai, ‘Orders in Stone: Social Reality and Artistic Approach. The Case of the Strasbourg South Portal,’ Gesta, Vol. 41, No. 2 (2002), pp. 111-128, footnote:70.

[iii] Simson 1972 p.37

[iv] Nicolai 2002 p.111-128

[v] Sara Lipton, 'The Temple is my Body: Gender, Carnality, and Synagoga in the Bible Moralisee' in Frojmovic, Eva, ed., Imagining the Self, Imagining the Other Visual Representation and Jewish-Christian Dynamics in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Period (Leiden: Brill, 2002).

[vi] Sara Lipton, Images of Intolerance: the Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible Moralisée (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), p.1; see also John Lowden, The Making of the Bibles Moralisées: The Manuscripts, Vol.1 (Pennsylvania: Penn State Press, 2000).

[vii] Gerald B. Guest, ‘Picturing Women in the First Bible Moralisée,’ in Insights and Interpretations: Studies in Celebration of the Eighty-Fifth Anniversary of the Index of Christian Art, ed. by Colum Hourihane, (Princeton: Princton University Press, 2002), p.106.

[viii] Rowe 2008; 2011

[ix] ibid. p.197

[x] ibid p.197

The Veiled Moses. Drawing. Anagogical window, St.-Denis, 12th century. Glencairn Museum, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania

The Veiled Moses. Drawing. Anagogical window, St.-Denis, 12th century. Glencairn Museum, Academy of the New Church, Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania

Cheryl Spinner

The Veiled Moses

https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/cs525-671project/long-long-history-of-veils/long-history-of-veils/moses-and-the-veil/

Ref. Britt, Brian. "Concealment, Revelation, and Gender: The Veil of Moses in the Bible and in Christian Art",

Religon and the Arts 7.3 (2003): 227-273.

Brian Britt’s “Concealment, Revelation, and Gender: The Veil of Moses in the Bible and in Christian Art” (2003) recovers the veiled Moses figure, a model of revelation that is not only neglected, but even avoided in Judeo-Christian tradition. Britt traces Christian and Jewish commentaries on the episode of the veiled Moses, beginning with, most importantly, Paul’s commentary on the relationship between Christ and the veil of Moses. According to the Pauline reading, Moses veils himself before the people of Israel to keep them from gazing at God’s glory; Jesus lifts the veil. In this understanding of revelation and divine communication, the figure of the Veiled Moses represents the Jews, who have yet accept Jesus. Theologically, then, the veil assumes a pivotal place in solidifying the difference between Christian and Judaic identities; yet, curiously, the veiled Moses is seldom depicted in Christian art. In his survey, Britt is only able to find eight images that depict Moses in the veil: the Vivian Bible, an eleventh-century liturgical manuscript, the Farfa Bible, St.-Denis Window, Queen Mary Psalter, Berlin History Bible, Botticelli’s Fresco, and a contemporary children’s book illustration. These images, which vary from depictions of Moses with a veil completely obscuring his face, to images that depict him half-veiled or not veiled at all, illustrate the myriad of ways in which this episode has been treated in Christian art.

The St.-Denis Window and the eleventh-century liturgical manuscript have been excerpted here, respectively, to the demonstrate just how varied these images are in their treatment of the Veiled Moses. Images like the St.-Denis Window, which cover Moses’s face entirely, are rare. Of the few that actually represent Moses with a veil, his face is often partially veiled or even fully revealed, with a veil nearby. In his survey, Britt wonders why Christian art seldom represents the Veiled Moses, and when it does, most are half-veiled. Still working within the tradition of the Old Testament, Britt argues, Christians would find the feminized depictions of this important Biblical figure particularly unsettling. Moses, after all, is the giver of the Torah/Bible, and despite his limitations for a Christian theology, he is still important and must be respected. Synagoga, the feminine personification of the Jewish people, usefully comes in as a surrogate for the veiled Moses. Complete with broken tablets and a blindfold, Synagoga can easily represent the Jewish people and their blindness without having to situate this within Moses’s male body. Moses, in turn, is represented with horns—itself a mistranslation of Hebraic word, “keren,” which is used to describe the rays of light that emit from Moses’ face once he descends from the mountain. With Synagoga the surrogate of Moses, the binary of “female as evil and male as good” is kept tidy: the fallen, veiled woman represents Judaism; the unveiled, albeit deformed, masculine figure can accept the Torah. It is thus simpler for a Judeo-Christian tradition to avoid the to troubling Veiled Moses figure altogether than to deal with the anxieties that are created by having to come to terms with Moses in female garb.

The Repressed Veil in Judeo-Christian Tradition

"Few interpreters in Jewish or Christian tradition have explored the religious richness of Moses’s veil, a biblical episode that alternates between presence and absence, concealment and revelation. To “read” the veil in writing and images is thus to “read” texts about revelation. Worn after his conferences with God and the people of Israel, the veil signifies Moses’s work as a prophet. But if the face is essential to personal identity, then the veil dissociates Moses from his prophetic office. For post-biblical tradition, this separation was too high a price to pay for fidelity to biblical tradition. The veil was either ignored, removed, or marked as punishment. Through a survey of these traditions of the veil, I will suggest that the repression of the veil entails a repression of text and textuality, and that the repressed veil and the text nevertheless resurface in transformed ways, especially in veiled female figures" (227-228).

The Veiled Moses. Städelsches SKunstinstitut, Inv. 622, fol. XI (Swarzenski, Die Illuminierter Handschriften, pl. v).

Anxiety and the Veil

The Veiled Moses. Städelsches SKunstinstitut, Inv. 622, fol. XI (Swarzenski, Die Illuminierter Handschriften, pl. v).

Anxiety and the Veil

"Of the few documentary and artistic renderings of Moses’s veil, most of them, following Paul, take the veil off, so to speak. Why is there such reluctance to show Moses with a veil on his face? If I am correct that the central concern of the Exodus episode is Moses’s role as prophet, then the veil introduces an element of silence and disempowerment at the very moment when Moses is supposed to be reinstating the covenant and his own authority as a prophet. Whatever the veil means, my assumption is that its role in Exodus and subsequent tradition reflects significantly on ideas of revelation. I will suggest that the avoidance of the veil by interpreters and artists bespeaks anxiety before the veil. In Christian art, this anxiety takes a number of forms, especially the preference to show the veil only partly covering Moses’ face, as well as an apparent preference to depict the Pauline veil on the female allegorical figure of Synagogue" (228, 229).

"As a metaphor for a negative moment in the process of revelation, the veil of Moses has analogues in religious traditions of silence, mysticism, the via negativa, and negative theology. But these traditions developed in the post-biblical tradition and make few references to such biblical motifs as the veil of Moses. The silence about the veil is not simply inadvertent but also a kind of anxiety. Anxiety, according to Kierkegaard, is a “dizziness of freedom, which emerges when the spirit wants to posit synthesis and freedom looks down into its own possibility, laying hold of finiteness to support itself.” This freedom is the freedom to encounter the veil of Moses or to reject it. The anxiety before the veil corresponds to an anxiety before the text, for as the tradition of rereading Moses’s veil shows, how Moses is read can determine nothing less than how the Bible is read, and the status of Moses is tied directly to the status of the Torah. To accept a version of Moses who is disempowered and hence feminized, by a veil, was almost always too costly a bargain for Jewish and Christian interpreters. But to encounter the veil episode of Exodus is to accept ambiguity, silence, and an endlessly paradoxical idea of revelation" (264).

Synagogue as Feminine Surrogate

"It was more common to imagine Jewish blindness as Synagogue than as Moses, in part because of her sex. For a culture in which men define women, there is something tidy and familiar about the binary choice between Church and Synagogue, good and evil. It was culturally easy to project the simple opposition in female form: Roman art often personified abstractions in idealized female figures, in portraits of goddesses, caryatides, and personifications, and women were seen typically in two-dimensional terms as either venerable or villainous. And while veils and blindfolds are not necessarily feminine in medieval art, covering the eyes and face is certainly disempowering. Moses may be inferior to Christ, but he’s a guy, and a powerful one at that. The frequency of the female Synagogue and the scarcity of the veiled Moses reflect the Christian feminization (and denigration) of Judaism. It was much easier to represent the spiritual failings of the Jewish people in female form, a stereotype that persisted for centuries" (Britt 260).

Moses receiving the Law and Synagoga, La Somme le Roy (popular compendium of doctrine), c. 1295. Paris, Bibl. de l'Arsenal, 6329, fol. 7v.

Moses receiving the Law and Synagoga, La Somme le Roy (popular compendium of doctrine), c. 1295. Paris, Bibl. de l'Arsenal, 6329, fol. 7v.

See also

The Minister’s Black Veil (1836)

Bible moralisée

The

Bible moralisée is a later name for the most important example of the medieval picture bibles to have survived. They are heavily illustrated, and extremely expensive, illuminated manuscripts of the thirteenth century. They were similar in the choice and order of the Biblical texts selected, but differed in the allegorical and moral deductions drawn from these passages.

Though large, the manuscripts only contained selections of the text of the Bible, along with commentary and illustrations. Each page pairs Old and New Testament episodes with illustrations explaining their moral signicance in terms of typology.

There are seven surviving manuscripts of the

Bible moralisée group; all date from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries and were designed for the personal use of the French royal family. Four were created in the early thirteenth century, when church art dominated the decorative arts. As common in stained glass and other Gothic art of the time, the illustrations are framed within medallions. The text explained the theological and moral meanings of the text. Many artists were involved in the creation of each of the

Bibles moralisées, and their identities and shares of the work remain unclear.

Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

This beautiful illuminated manuscript, now in Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, is one of the earliest surviving examples of a unique group of Bibles containing the most extensive cycles of biblical illustrations juxtaposed with theological and allegorical interpretative images. The present moralized Bible was produced in Paris in the first half of the 13th century, and contains over 1000 exquisitely illuminated medallions accompanied by textual extracts and commentaries that act as captions to the illustrations and thus reveal, by word and image, the relevance of the Bible to contemporary life. They reflect the rapidly-changing world of the thirteenth century and highlight the many ideological problems prominent in the intellectual and political milieu of the time. It is a book that has long fascinated both historians and art-historians, since it stands out not only as one of the major artistic achievements of its time, but also as an important historical document for an understanding of medieval Europe.

The moralized Bible, in which biblical scenes are juxtaposed with theological and allegorical interpretative images, was a new and original type of biblical manuscript that emerged in Paris in the 1220s. The book reproduced in the ÖNB in one of the most beautiful of the surviving copies that was made in the firt half of the 13th century, and its glorious pages, with over 1000 illuminated medallions, vie with the translucent stained glass windows of the great Gothic cathedrals.

Each manuscript page has eight roundels (circles with illuminations). Four of the eight roundels contain illustrations of the biblical scene. Each of these four have a corresponding illustration of the contemporary spiritual significance of the scene. This "spiritual significance" often contains a moralistic interpretation of the biblical scene - hence the name, Bible Moralisée.

The Jews throughout the volume are distinguished for easy visual comprehension by their pointed hats and money sacks. Entire books have been written about the depiction of Jews in these bibles for these texts are treasure troves of contemporary Medieval cultural information.

Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Codex 1179

Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Codex 1179

Sara Lipton,

Images of Intolerance: The Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible moralisée, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999, pp. 15-19.

One: A Discernible Difference

Humanity is rigidly divided into good and bad. The representation of "good" is characterized by order and regularity: the figures are uniform in size, dress, and gesture; serene in expression; focused in gaze; and carefully organized in their placement. They are encompassed within a circular crenelated structure, which signifies the unity, but also the exclusiveness, of the Heavenly City. The "bad" are, in representation as well as by definition, all that is opposite to the "good." They are literally "outsiders," situated outside the walls of paradise. They are inconsistent in size, dress, and gesture; their varying expressions indicate distress, regret, and indifference. They are also alien to each other: gazing up, down, to the right, and to the left, but in no case interacting. One carries a moneybag; two wear crowns of thorns; and a third, dwarfing the rest, wears a tall, pointed red cap. These three attributes especially bring us to the subject of this book, for each is in its own way (in the closed world of these manuscripts, but also beyond) a symbol relating to Jewishness. Why the crowns on the heads of the "bad" imperfectly mimic those of the good while recalling the headgear of Christ himself, why physiognomically and sartorially diverse figures are each endowed with a sign of Jewishness, and especially why the figure of a Jew looms over this gathering of the "bad" can be answered only by careful study of all the techniques for signifying "otherness" displayed in these rich and complex manuscripts.

Gen 2:8-9. The good, crowned with flowers in paradise, and the bad, cowned with "thorns of the world." Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Codex 2554, fol. IVd (Lipton, fig. 1) .

Identifying Jews: The Pointed Hat as Signifier and Sign

Gen 2:8-9. The good, crowned with flowers in paradise, and the bad, cowned with "thorns of the world." Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Codex 2554, fol. IVd (Lipton, fig. 1) .

Identifying Jews: The Pointed Hat as Signifier and Sign

The keynote of the iconography of Jews and Judaism in the

Bible moralisée is ambiguity; it is no simple matter to isolate references to Jews in either the text or the images. Many names are used for Jews, figures may bear only some of the visual attributes assigned to Jews, and the attributes may be equivocal, or even entirely absent from characters apparently intended to be read as Jews. A similar ambiguity is evident throughout the

Bible moralisée in images dealing with almost every imaginable subject [...]. I argue this ambiguity of representation is both intentional and meaningful.

The ambivalence of the textual and visual commentary serves to deepen and make flexible the meaning of the Bible--a common approach in high medieval exegesis and, indeed, a necessary project for any intellectual endeavor designed to present antique Hebrew scriptures as a blueprint for all aspects of medieval Christian life. At the same time, the abstruseness in the treatment of the Jews in these manuscripts bears witness to and seeks to control a range of very real social and religious ambiguities that seem to have been viewed as menacing by the clerics involved in the making of the

Bible moralisée.

Nevertheless, a "standard" method for depicting Jews can be identified in the manuscripts and may serve as a norm by which to assess the more complex representations. In the images accompanying texts that refer explicitly to Jews, the roundels generally show bearded men wearing various forms of a conical or pointed hat (

pileum cornutum). This representation is, of course, not unique to the

Bible moralisée; the use of the pointed hat as a Jewish attribute in medieval art dates back to the eleventh century and by the thirteenth century was widespread and conventional. In the

Bible moralisée, the "Jew's hat" takes various shapes: it may be very tall and sharply pointed; it may be of the so-called oil-can type (broad-brimmed with a knob at the top); or it may be soft, low, and only slightly peaked. This last type is identical to the headgear of many Christian figures, begging the question of to what extent it is a "Jew's hat" (as opposed to the hat of a Jew) at all. [...]

Although it has long been accepted that the pointed hat was the standard Christian iconographic convention for identifying Jews thoughout the High Middle Ages, there is still disagreement concerning the full significance of this sign in Gothic art. Some scholars have noted that Jews were depicted wearing the pointed hat in the Jew's own Hebrew manuscripts and have concluded that the depiction of the Jewish hat in art was mimetic, that is, a faithful documentation of historical reality bearing no spiritual import. Others have asserted that the sign was employed primarely as a pejorative identifier and almost inevitably carried an anti-Jewish connotation.

The first assertion is not convincing, as far as French Gothic iconography goes. The

pileum may have been worn by Jews (as well as by other peoples) as early as the ninth century B.C., but it is doubtful whether by the thirteenth century Jews in northern France regularly wore the pointed hat or, indeed, covered their heads at all. [...] Canon 68 of the Fourth Lateran Council, which called for the imposition of distinctive clothing on Jews, began with the statement: "In some provinces a difference of dress distinguishes the Jews ans Saracenes from the Christians, but in other confusion has developed to such a degree that no difference is discernible. It seems likely that the Jewish communities of northern France, by no means the least assimilated of European Jewries, included members who were visually indistinguishable from Christians. The use of the pileum as an iconographic attribute of the Jews, then, was not based on actual practice but was an external and largely arbitrary sign devised by Christian iconographers in order to create certain modes of perception. Precisely because the position of Jews in late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century Europe was not exactly what the dominant stream of clerical ideology--that informing the canons of the Fourth Lateran Council--determined it should be, the Jew in works such as the

Bible moralisée is generally, though not inevitably, made identifiable in a way that the Jew in Christian society was not. Like the provisions for distinguishing clothing imposed by the Fourth Lateran Council, the use of the

pileum in Christian art was an attempt to visually codify a certain attitude toward Jews.

This ongoing tension between the Jews' constructed Otherness and actual visual sameness is evident in the jews' clothing. Jews are rendered in a variety of clothing styles in the

Bible moralisée. [...] Christians are depicted wearing similar clothes in the manuscripts, and it is impossible to identify a figure as a Jew from his clothing alone. This situation mimics the confusion that occasionally arose from the similarity of Jewish and Christian dress in real life--confusion that clearly was a source of concern to some members of the Church hierarchy. [...] The conceptual anomaly presented by diametrically opposed spiritual groups displaying similar outward appearances posed a threat to proper order and hierarchy.

However, the assumption that the pointed hat clearly and unavoidably conveyed anti-Jewish polemic is equally problematic. It does not seem that the hat was regarded as a degrading object by medieval Jews: they had themselves portrayed wearing pointed hats in their own manuscripts, and they used the pointed hats on their own seals and coats of arms. Nor can the use of any particular article of clothing to identify the Jews as a group necessaribly e considered an anti-Jewish practice, for many social groups were iconographically distinguished in medieval art. [...] The fact that Old Testament patriarchs and prophets as well as certain revered New Testament Hebrews such as Joseph, Joachim, or Joseph of Arimathea are depicted with Jewish hats would argue against any

automatic negative connotation. On the other hand, a self-contained sign system can, of course, construct a polemical message though the development and elaboration of a traditional iconographic motif. Just such a development is detectable in regard to the pointed hat in the

Bible moralisée manuscripts. [...]

The most basic function of the pointed hat in the

Bible moralisée is simply to denote the concept "Hebrew" [...] or "Jewish identity" [... but it can also signify] "being like a Jew" [and thus representing deceit]. [... The hat-as-sign becomes a sign for complex ideas and can convey] opposition to Christianity, fraud, unbelief, [and even] diabolical connexions. [...] The concentration of iconographic interest in the hat is telling: the hat does not just identify Jews; it functions independently of its placement to signify infidelity and recalcitrant Jewishness.

Tob. 11:10-11. The conversion of the infidels at the end of the world. Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Codex 1179, fol. 181a (Lipton, fig. 4).

Tob. 11:10-11. The conversion of the infidels at the end of the world. Bible moralisée, France, 1215-30. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Codex 1179, fol. 181a (Lipton, fig. 4).