Loos, a vigorous denouncer of ornament and the great cultural moralist in the history of European architecture and design was a revolutionary against the revolutionaries. With his assault on Viennese arts and crafts and his conflict with bourgeois morality, he managed to offend a whole country. He launched his controversial views in 1897 through a series of published essays, which addressed the excesses of traditional Viennese design, particularly as exercised by the

Jugendstil movement (

Vienna Secession, led by

Olbrich and

Hoffmann). These theories culminated in 1908 with the publication of a short essay entitled "Ornament and Crime." To Loos, the lack of ornament on architecture was a sign of spiritual strength, an aesthetic beauty that only those who lived on a higher level of culture would appreciate. According to him, "The urge to ornament oneself and everything within reach is the ancestor of pictorial art. It is the baby talk of painting... the evolution of culture marches with the elimination of ornament from useful objects."

Joseph Rykwert,

Adolf Loos: The New Vision,

Studio International, vol. 186, # 957, 1973

Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos (1870-1933) was not the finest architect of the century. But amongst twentieth-century architects, he was probably the only one (with the possible exception of

Le Corbusier) to be a major writer.

His family was unremarkable, though his background was a strong influence. He was the son of a prosperous craftsman: a monumental mason who had been very conscious of the dignity of his trade. He had practised this trade of his and lived in Brno, on the border of the Czech and German-speaking Habsburg lands. Adolf Loos was born there in 1870; he was therefore 48 when the Habsburg Empire fell. He died in 1933, the year of the Nazi rise to power, a deaf, broken man in spite of his relatively young age. His writings were marked by the feeling their titles summed up:

Ins Leere Gesprochen and Trotzdem (Spoken into the Void, and Nonetheless). The sense of contradiction is inherent from the outset. Loos had been – surely more than his father even – aware of the nobility and worth of the paternal calling. But his father had died when Loos was just over ten years old, and his veneration for his father's memory contrasted sharply with his distaste for his mother's ways, her drudging insistence on security and achievement. The army, the art-school and finally the American journey liberated him, severed the family ties and formulated his resolve to become an architect. Already, when he was a student at the Dresden Gewerbeschule, he showed his mettle. Unlike most of his contemporaries, he rejected the servitude of the fraternities and the brand of a duelling scar that went with it. It was not only his distaste for the philistine ways of most of his student contemporaries, but also a fastidious care for personal propriety and integrity which motivated him. And his civil courage was already firm.

The fastidiousness was already in evidence when he first went to do his military service in Vienna. Leather and silver objects of high quality became his passion. The designers of that time regarded surface as a free field for the ornamental inventor. Curves, lines, inlays of varied materials covered all available plane surfaces. Instinctively, Loos already sought the smooth, the barely chamfered or edged. A passion for smooth and precious surfaces was an instinctive preference – which, as I will try to show, he later rationalized. His period at arts-and-crafts schools had left him with an interest in ornament – as he recognizes in one or two autobiographical pieces; but when he returned to Austria, his taste had been cleared by the sharp, clear Anglo-Saxon air he had breathed. And he rejoiced that the sensible Viennese bourgeoisie had rejected the fancy ornament which had become so popular in Germany and France. He was, of course, a mythomane. His idea that ‘the American kitchen never smells of onion, that the American woman can prepare the most exquisite meal in a quarter of an hour; she twitters like a bird and always smiles ...’ could not be the product of much direct experience; in spite of the visits to Philadelphia cousins, his stay in America seems to have been taken up with nights washing-up in restaurants, living in the YMCA and poor lodgings, some journalism and occasional recourse to the breadline. But those three years in the United States did form Loos's view of what he was about decisively. He was to be an architect, and in that sense a builder like his father. But he was also to bring to Vienna the inestimable gift of western culture; his little magazine (of which only two numbers appeared)

Das Andere (The Other) had as its subtitle ‘a paper for the introduction of Western culture to Austria’. This Western culture had a curious physiognomy. Its structure could not be described; it was made up of surface details, which together gave the outline of a fabled and highly desirable state of affairs. Look at the matters with which

Das Andere dealt: clothes, manners, table manners in particular; begging; sexual mores among the very young; the overdecoration of Wagner's Tristan in the Vienna Opera; the ill manners of the very great (the Emperor Wilhelm II is named); street decorations for state visits and so on.

All the time, the manners of the Anglo-Saxon countries are assumed as a model, as a standard of reference. The right way to do things is the way they are done at the heart of civilization, and that was either in London or in New York. By comparison with their ways, Austrian manners are found wanting at every point.

Much attention is paid, for instance, to the lack of spoons for the salt-cellars of Viennese restaurants. And, sometimes, this insistence is taken to extreme lengths: Loos rediscovers the aubergine, familiar in Europe since the sixteenth century, as the American egg-plant; and arranges to have American-type aubergine fritters served daily for a week in a named vegetarian restaurant in the hope of inspiring Viennese housewives and restaurateurs into emulation.

It may all seem very remote from Loos's central business of architecture. And yet for him it was not. Whenever he worked, he was always almost obsessively interested in how a building would be occupied. His great hostility to the Secession, the group of anti-academic Viennese artists who were the Austrian branch of Art Nouveau, turned on this point also. Art Nouveau architects and designers thought that a new style could be created for their own time in terms of an ornamental vocabulary, which would have no relation to historical ornament, but would be drawn entirely and directly from nature. Some went even further. They thought that this ornamental surface could be applied not only to walls, windows, floors, and pieces of furniture, but also to clothes and even to jewellery in a scientific fashion, so as to stimulate or reflect emotional states.

In some ways, this attitude to ornament had its source in the psychology (and later the aesthetics) of empathy, a teaching still not wholly dispensable, according to which we ‘read’ our state of being into the objects which surround us, and in a particularly heightened form when these objects present the pressing claim to our attention which works of art inevitably do. While this idea stimulated the particular researches of certain designers such as

Henry van de Velde, for whom Loos reserves his most withering scorn, the notion of style which can be summed up in terms of its ornamental patterns is an idea formulated — among others — by the great German historian and architect, Gottfried Semper. Clothing, he believed, was the primary stimulus for all figuration. Clothing understood not only as protection, but also as the adorning of the human body. Semper was perhaps the first to consider tattooing among the arts of mankind.

Tattooing obviously fascinated Loos. In the most famous of his essays, the one on ornament and crime, he holds the Papuan up as an example of man who has not evolved to the moral and civilized circumstances of modern man, and who will therefore kill and consume his enemies without committing a crime. Had a modern — meaning a Western man — done the same thing, he would either be considered a criminal or a degenerate. By the same token, the Papuan may tattoo his skin, his boat, his oar or anything he may lay his hands on ... He is no criminal. But a modern man who tattos himself is either a criminal or a degenerate. Tattooed men who are not imprisoned are either latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats. If a tattooed man dies free, this is because he has died prematurely, before committing his murder.

Horror vacui is the origin of all figuration. ‘All art is erotic’. But man has evolved. And Loos proposes the axiom that the evolution of culture is equivalent to the entfernen of ornament from everyday things. Writing this essay as he did in 1908, it was easy to dismiss the elaborate confections of Van de Velde and

Otto Eckmann, or even

Joseph Olbrich, as worthless. Art Nouveau was already a thing of the past. Loos's contempt for their efforts had proved justified, while art schools, ministries and professional bodies were still intent on the study of ornament. But even in Loos's triumph, there is an element of inconsistency. His shoes, he admits, are covered with ornaments. English-style brogues, one must suppose. Loos imagines offering his shoemaker a premium price for the shoes: a quarter more than usual, and the delight of the shoemaker at having such an extremely appreciative client. But were he to ask the shoemaker to make the shoes quite smooth, without any ornament, he would topple his shoemaker from the heaven he had raised him to by his offer into the deepest hell.

The creation of ornament is the shoemaker's pleasure. And that, Loos thinks, is what makes it acceptable. ‘I can put up with ornament on my own body even, if it is a witness to the pleasure of my fellow-man’. Brogue shoes, Balkan Kelims, all that is tolerable, even welcome. But, says Loos, I preach to patricians. And patricians are those who — unlike his shoemaker — go after a day's work to relax listening to Tristram or to Beethoven. And a man who goes to listen to the ninth symphony and then sits down to draw a carpet pattern is either a confidence trickster or a degenerate.

The particular hate for the ornamental patterns of the Art Nouveau designers had a further motivation. Loos wrote the moral tale of the Poor Rich Man, who had his house, which he had hitherto inhabited so peacefully and contentedly, made into a work of art, since he had become discontented living without art. And the architect had designed every detail of the Rich Man's home, covered every surface with elaborate ornament; he anticipated everything, even the pattern on the Rich Man's slippers. The day came when the Poor Rich Man's family offered him birthday presents, which they had bought at the most approved arts-and-crafts establishments. The architect, summoned to find correct places for them in his composition, was furious that a client had dared to accept presents about which he, the architect, had not been consulted. For the house was altogether finished, as was his client: he was complete. The Poor Rich Man was written in 1900, at the height of the Art Nouveau phase. Loos's was then an unpopular, minority view among the cultivated; he seemed to take up cudgels for the philistines who still preferred their saddlework and their silver smooth and unadorned. By 1908, the year in which Ornament and Crime appeared, the climate of opinion had changed. Even the Viennese leaders of the Secession, like Joseph Olbrich, were working in a sober, ornament caste-shorn classical manner. Olbrich's last houses (he died in 1910) and Hoffmann's buildings — such as his pavilion at the Werkbund Exhibition of 1914 — align them with the more 'progressive' among the German architects: with

Peter Behrens,

Bruno Paul,

Hermann Muthesius,

Heinrich Tessenov.

But the ‘shorn’ classicism which they practised was not for Loos. They were the architects of — at that time at any rate — a confident bourgeoisie, which seemed to believe that the problems of Germany (and by extension of the rest of the world) would be solved in a reasonable way. That the Werkbund ideals of educated taste and good design would favour the expanding markets; and that all these good things would be fostered by the improving of art education on the English arts-and-crafts-school model.

The architects who held such ideas appealed to an architecture of reason for their precedent. The architecture of the age of reason, of the age of taste. Classicism, the brand of classicism which had evolved in Germany and Austria in the wake of the French masters, and culminated in the work of

Schinkel, was the favoured model. But the apparently arbitrary slavery of neo-classical architects to an historical past was rejected. A model, yes, but to emulate, not to copy. Ornament, in any case, was considered something abstract; the ideas of the 80s and 90s, the notion that ornament and line could convey a mood or even a message, were alien to them. To Behrens as to Hoffmann, ornament was a modenature which might accentuate the play of light over the surface, at the most an anodyne echo of a generalized melancholy for the past, a garnish for the essential geometrics which — so it seemed to them — reason had always dictated.

Loos, like many of the architects of the pre-1914 period, was self-consciously modern. I have already noted this. And he had other things in common with them. His generous, if sometimes misguided, enthusiasm for all things English, for instance. But he was untouched by the generalized Werkbund optimism. It was not through the reformation of untutored mechanics in art schools, however excellent, that good design would be achieved throughout society. In so far as good design was available, it was those very rude mechanics, the saddler, the silversmith, the upholsterer, even the plumber — but above all the tailor and the shoemaker — who already provided a repertory of excellent objects for everyday use. This was the early intuition of the perfection, of the superiority, of unadorned objects, as they had come from the ‘unspoilt’ craftsman's hands. Loos remained consistent in this: if you look through his interiors, whether private or commercial (he never designed a public building) you will find that he never used ‘modern’ designed furniture. His preference was for English style, for Chippendale or Hepplewhite chairs; or else the cheaper canework. Occasionally he uses the standard Thonet chairs in bentwood, familiar from cheap cafes all over Europe. The armchairs are the usual cosy, sub-Biedermeier upholstery, even including the occasional Chesterfield. The floors were, for preference, covered with Oriental rugs.

I suppose that is why there are so few photographs of the house which Loos designed for the most famous of his clients, Tristan Tzara, in the Avenue Junot, on Montmartre. To the street the house would have shown — had the projected top storey been built — a great white square set over a rubble stone base. The base contained the garage and fuel store, as well as the main entrance on the ground floor, and the main windows of a flat for letting above. This flat was entered from behind the building. The main apartment consisted of hall and kitchen looking through the windows which overhung the string course, more important rooms in the huge niche, about half the height of the square and a third of its width, which cut sharply into the great white surface, a negative of the shape which he would later perfect in the Muller home at Brno. It was set in the middle, so that a swathe of white, a third of the square's width, went round it on three sides.

The inner complexity of the plan was a topical Loosian solution for a difficult site. The complexity had its wit, as did the strangely highly-abstracted anthropomorphism of the facade, or the use of the commonplace Parisian industrial detailing in the lower floors, the shape of the lower niche, again the inversion of his favourite English bay-window. It is a configuration not unlike Le Corbusier's exactly contemporary villa at Garches for Leo Stein: a blank facade, sparsely pierced to the street, and an open, glazed frame towards the terraces and gardens at the back. But Loos's complexity always remains hard, the spaces are never moulded, never the plastic, shaped interiors which Corbusier made them.

Repeatedly Loos asserted that the architect's business is with the immeuble, the craftsman's with the meuble. The architect saw to the inert volume, to the walls and ceilings and floors, to the fixed details such as chimneys and fireplaces (beaten copper was one of Loos's favourite materials). And here his haptic reading of buildings was most important.

Wherever he could, Loos used semi-precious materials on walls and ceilings: metal plaques, leather, veined marbles or highly veneered woods, even facing built-in pieces of furniture. But unlike his contemporaries, Loos never used these materials as pieces to be framed, but always as integral, continuous surfaces, always as plain as possible, always displaying their proper texture: almost as if they were a kind of ornament, an ornament which showed the pleasure providence took in making them, as the more obvious type of ornament would display the pleasure experienced by his fellow-men.

Curious then, this feeling for the decorative effect of figuring in the arch-enemy of all ornament. Even more curious is his persistent use of the classical columns and mouldings. The crassest of these was his project for the Chicago Tribune, an unplaced competition project; it was an extraordinary scheme which consisted of a vast Doric column, (the shaft alone 21 storeys high) on a high parallelepiped base. To Loos, however, the project seemed wholly serious. The building was to be a pure classic form, classic and therefore outside the reach of fashion, so that it would fulfil the programme of the competition promoters to 'erect the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world'.

A naughty extravaganza you might say. Of course. But Loos was convinced, secure enough, to allow himself that also. He had imagined a way of life in the house. The felicities of the plan all exult in the way the house was to be occupied, to be lived in. And does everything to ennoble it formally by a quiet unassertive wit. It is at this scale that Loos was at his happiest. The private houses are his masterpieces: they, the bars, the clothes shops, all buildings on a small scale, for the greater dimensions of public urban building he could not quite master. Though perhaps this is not entirely fair to him. In 1920 he was appointed chief architect for the Siedlungen of the post-abdication, the newly Republican Vienna. It was the nearest he came to giving positive expression to the western civilization he spoke of in architecture. But he was consumed by one or two detailed ideas which he never fully worked out: the terrace house with weight-bearing party-walls, and light construction cross-wall (what he called ‘the house with one wall’); the use of stepped terraces, so that the roof of one house could serve as garden to the next; the provision of access at every other floor, so that the terrace became in fact an immeuble villa, to adapt Corbusier's phrase. But his appointment did not and could not last. Only one of his Siedlungen was actually built, only partly following his plans before he retired, disappointed and embittered, to Paris. It is too easy to say that it was fated, that he should have remained the architect of the individual villa. Although all his projects for great public buildings show him at his worst, the low income housing absorbed his ingenious talent, drew the egalitarian and the moralist in him to a full engagement.

However, although the failure was primarily political, there is in the projects a kind of naivete, a concentration on the passage from one material to another, the lack of a sense of urban context for them, the absence for want of a better word, of a sense of structure. After all, the pleasures of his architecture are the pleasures of touch. And yet he was dimly aware of a mystery beyond, a mystery which he could not quite name. ‘All art is erotic’, he had written in Ornament and Crime. The erotic element in art had to be sublimated, however. The man who scrawls explicit erotic signs on walls is, again, a criminal or a degenerate, like all tattooers of surface. And yet, ornament cannot be dismissed altogether, for in the end the business of architecture is evocative. In attempting to get closer to this idea, he fell into a strange figure. ‘When, in a wood we come on a mound, six foot long, three foot wide, heaped up into a pyramid with a spade, then we become serious and something says inside us: someone lies buried here. That is architecture’.

Obsessionally almost (and in his later years ever more despairingly), Loos followed the ideal of an architecture which could communicate; communicate about this perfect way of life which seemed to him realized in the Anglo-Saxon lands, in his paradise. He never attempted a systematic view, a coherent theory of architecture, or of anything else for that matter. He was obsessed with immediate sensations as ingredients of a perfect way of life. The quality of smell and of touch, the juxtaposition of textures, the passage of an inhabitant from one volume to another, all these he observed with a sharp and loving eye.

Beyond this, and more gropingly, he sought for an architecture which could communicate and reconcile man to his fate. Though again it was not man in general with whom he concerned himself, but the same inhabitant of his buildings whose senses he wanted to stimulate and soothe. And beyond him, the passer-by: every building of his is not a maze which traps a way of life, but a presence which communicates with its inanimate neighbours.

It is these two passions which make him so fascinating a figure: since he tried to capture and celebrate things which his contemporaries had taken for granted, and were discarding in the name of progress. And which — now that they are lost — we miss in a way our fathers, his contemporaries, would never have imagined.

Ornament Returns

Ornament Returns. Exactly 100 years after Adolf Loos wrote Ornament and Crime, a manifesto that effectively relegated ornament in architecture to the peripheries of the discourse, "Re-sampling Ornament" takes a first step towards tracing its re-emergence. For decades the language of architectural ornament has remained largely unspoken, but for a few memorable post-modern architectural experiments. Yet from Owen Jones 'Grammar of Ornament' to John Ruskin, Gottfried Semper, Louis Sullivan and William Hogarth – and contemporaries such as Kent Bloomer, a rich vocabulary of opposing and often contradictory theories exists to be readapted, re-sampled, and once again applied at the heart of architectural practice.

Oliver Domeisen's research at his unit at London’s Architectural Association into the history and contemporary application of ornament in architecture has made it possible to embellish and enrich a mutual selection of new architectural projects with terminology drawn from many dictionaries; allowing for associations and groupings that can identify vital traces of ornament in current practice and at the same time rethink its boundaries, creating a new context within which contemporary projects can be redefined and rethought.

Whilst the ideological rigor of Modernism once rejected the supposed decadence and wastefulness associated with the mass production of ornament, it is undeniable that over the past 10 years entirely new construction and manufacturing processes have made the return of ornament economically viable. 3D computer modelling can now steer mass-customisation processes from CNC milling to laser cutting.

Ornament is the home of metamorphosis uniting and transforming conflicting worldly elements. It is an image of combination and a spectacle of transformation. Ornament is a method to subsume almost anything into the architectural idiom: human bodies, plants, militaria, microscopic patterns, fantastical beasts – it is the realm of monsters and hybrids. Ornament is transgressive. It sits comfortably between realism and abstraction, antiquity and modernity, mechanical objectivity and artistic subjectivity, convention and expression, and the real and the ideal.

Crucial to a new reading of ornament in architecture is its enduring relationship to nature. “Re-sampling Ornament” reasserts the right to enjoy the intelligent conceptual play with beauty and to rediscover sensuality in current manifestations of ornament in architecture. According to the architectural historian Kent Bloomer, there are malleable and erotic 'Bio-Keys' that span cultures and histories, as though there were some deeply rooted genetic code of ornament. Ruskin's "Curves of Temperance and Intemperance" sought the geometry of virtue in ornament, one that William Hogarth traces with scientific exactitude in the curvature of bones and the lines of a woman's pelvis. Today, computer-aided design can bring forth organic forms in architecture as well as stretching artifice to its extremes.

In our age of conspicuous consumption, brand culture also becomes a welcome resource for the architecture of ornament in all its opulence. The icons of our age are perhaps the logos that define the corporate world that surrounds us; the manufacturers of desire. The architects featured as defining new styles and languages to accommodate this iconography are distinguished by the elegance with which they resolve the dilemma of representation in unique ways – uniting ornament with a pertinent commentary on contemporary visual culture.

“Re-sampling Ornament” reinstates ornament in contemporary architecture with an abundance of new conceptual and aesthetic possibilities. Ornament operates trans-historically and trans-culturally. It is constant dynamic movement and expansion. Ornament is not truth – it is mimesis, material transubstantiation, deception, artifice, pleasure and beauty that render utility acceptable (

SAM-Basel, 2008).

Johannes Esaias Nilson (1721-1788),

Neues Caffehaus (New Coffee House), colored copper engraving, Augsburg, Germany, 1756.

The art manifesto has been a recurrent feature associated with the avant-garde in Modernism. Art manifestos are mostly extreme in their rhetoric and intended for shock value to achieve a revolutionary effect. They often address wider issues, such as the political system. Typical themes are the need for revolution, freedom of expression and the implied or overtly stated superiority of the writers over the status quo.

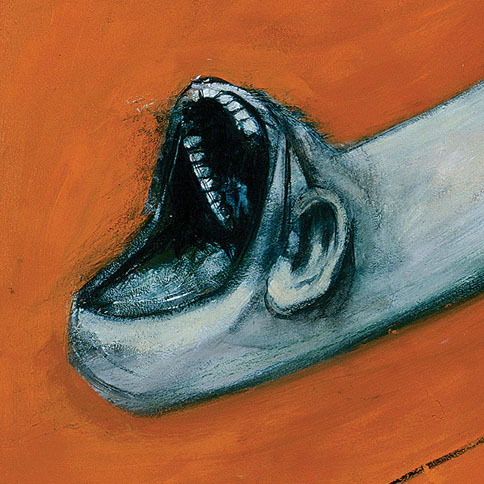

The art manifesto has been a recurrent feature associated with the avant-garde in Modernism. Art manifestos are mostly extreme in their rhetoric and intended for shock value to achieve a revolutionary effect. They often address wider issues, such as the political system. Typical themes are the need for revolution, freedom of expression and the implied or overtly stated superiority of the writers over the status quo. 7. Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

7. Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.