Josef Maria Olbrich, The Secession Building

by Dr. Laura Morowitz

A New Freedom for Art

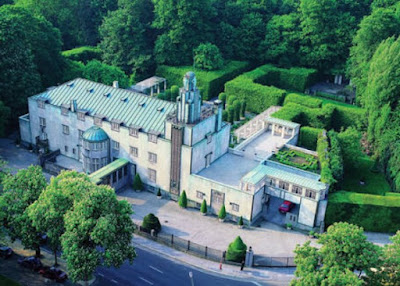

Imagine yourself walking down the street in Vienna and coming across the Secession Building. It’s oddness would likely stop you in your tracks. It certainly looks like nothing else around it—no school, no church, no government building. It’s gleaming white walls, lack of windows, gilded inscriptions and strange floating sphere of golden leaves looks like a temple built by some secretive, mythic people who long ago disappeared.

Architect Josef Maria Olbrich’s building perfectly expressed the aim of the group for whom it was built, the Vienna Secession: to set themselves apart, to shock and put forward a new form of beauty, something at once profoundly modern and as old as human nature. The Secession— a term meaning “to break away”—formed in April of 1897 when a number of members within the Association of Austrian Artists departed in frustration. These artists, architects, and designers had grown tired of nineteenth-century ideals and beliefs such as historicism (the constant reference to the past in art), positivism (a focus on that which can be rationally or scientifically proven), realism (a focus on art that creates an illusion of reality), and the commercialism of art (the idea that artists were working strictly for profit, rather than a more noble calling).

The Secession referred to the Union of Austrian Fine Artists (Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs). Painter Gustav Klimt was nominated as President and original members included architect Josef Hoffmann and designer Kolomon Moser. The central credo of the Secession was emblazoned in gold above the doorway: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst/Der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To Each Age its Art/To Art its Freedom). With this rallying cry the group made clear that it was the task of artists of each new generation to find their own language and subjects to express the moment in which they lived, rather than to constantly recycle the past. Throughout the nineteenth century, architects like Charles Garnier had created historicist buildings which drew upon both classical and baroque styles; the members of the Secession saw this as inherently dishonest. For them, art stood above politics, above commerce, and above ideology.

Exhibiting the New

Olbrich’s Secession building was the site for all the exhibitions of this group, beginning in October of 1898. Rather than nodding to periods or styles glorified in the nineteenth century, such as the High Renaissance or classicism, the building evokes other styles, including those of archaic Greece (as opposed to the art of the classical period) a style embraced in Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze in the interior) as well as other Mediterranean civilizations like ancient Egypt. The stretch of flat walls, made of plaster covered in whitewash, recalled the city walls and friezes of ancient Assyrian and Egyptian palaces and the strange proportions of Olbrich’s building include distant echoes of pylons (the gateway of ancient Egyptian temples). The forms of Western architecture—columns, arches, sloping roofs— are nowhere to be found.

Many commentators of the time found the open metal work sphere at the top, composed of 3,000 golden leaves, and recalling both laurel-leaf crowns and the thinly hammered gold jewelry of ancient Mediterranean, to be the strangest of all. The weirdness of the building earned it some memorable nicknames in its time including “Mahti’s tomb” and “The Golden Cabbage.” In addition to their rallying cry, the name of the group’s journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), is written on the building.

Like the title, the three Greek gorgon masks that hover above the doorway evoke the world of archaic Greek art. The play of austerity against elements of decoration, like the stylized trees with gilded leaves is characteristic of the style of many artists within the early Secession, in media including architecture, ceramics, jewelry, painting and the graphic arts.

Inside the building, the innovative architecture continued. It was the first exhibition space designed with movable walls to accommodate different types of work. Beginning in 1898, the Secession held annual exhibits where the most innovative art, not only in Vienna, but throughout Europe, was put on display. It was one of the only spaces within Austria where artists could see a full range of the European avant garde including the work of artists like Honorary Secession members Fernand Khnopff, Edward Burne-Jones, and August Rodin. In addition to Klimt, Secession artists such as Hoffmann, Moser, and Otto Wagner would form the heart of Viennese Modernism in the arts and architecture. Perhaps the most famous of the Secession exhibits was the XIVth one, in 1902, devoted to the German composer Beethoven.

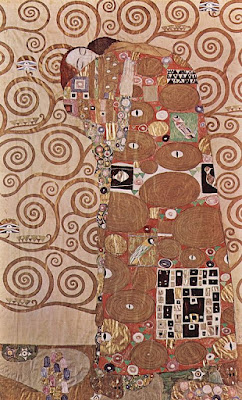

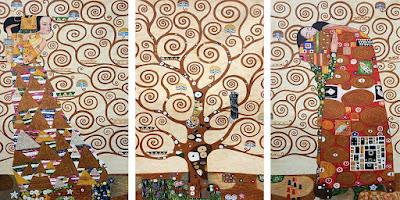

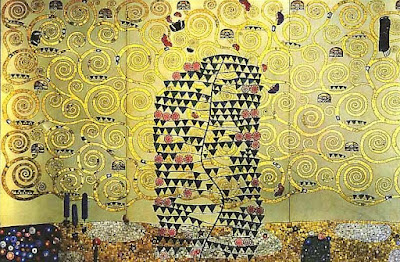

The entire building was turned over in tribute to him, with a sculpture by Max Klinger and Klimt’s enigmatic Beethoven Frieze painted around the upper walls of one gallery. The work was inspired by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, played by Gustav Mahler at the opening of the exhibition, creating a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art—inspired by composer Richard Wagner’s concept where many art forms combine to express a unified vision.

A bridge between the old and the new

The work of the Secessionists was innovative and scandalous in its formal experimentation, for example in Moser’s woodcut for an 1899 cover of Ver Sacrum, with its non-naturalistic colors, flatness, surface design (as in the closely related Jugendstil), and simplified, bold drawing, at once elegant and powerful. It was also shocking in the way it dealt with new subjects and modern life in ways that were utterly shocking to the staid denizens of Viennese society; Gustav Klimt’s Hope I juxtaposed a nude, very pregnant woman with visible pubic hair, against symbols of death and decay. While some of the twentieth century’s greatest minds (including Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Arnold Schoenberg), were already at work in the city, Vienna was still the crown jewel of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had been ruled for decades by Emperor Franz Josef.

Writer Stephen Zweig captured the conservative nature of this culture when he noted that at twenty years, a man would know exactly what his life would be like at fifty. Into this stiff world of imperial pomp, elaborate waltzes and tight corsets, the members of the Secession displayed images of frank sexual desire, psychological fears, and morbid fantasies. For example, one of the most common motifs of Secession members was the femme fatale, the deadly seductive woman who reigns in the works of Klimt, Felicien Rops, Ferdinand Khnopff and others.

In many ways, the art produced during the early Secession, like Olbrich’s building, is a bridge between nineteenth-century Academic art and the abstraction that would come in the twentieth. Academic art refers to the manner and style taught in the European art academies of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, rooted in the classical art of Greece and Rome. Works produced in the academies were highly finished, naturalistic, and greatly idealized, like Frederic Leighton’s Bath of Psyche, painted for the British Royal Academy. The enticing, languid figures of the early Secession hark back to Academic ideals of beauty, but begin to abandon the traditional, illusionistic language passed down from the Renaissance.

The work of the Secessionists was often still tied to nineteenth-century ideas of beauty and sophistication, in contrast to the artistic movements that would emerge in the second decade of the twentieth century, like the Futurists or Die Brücke. For all its oddity, Olbrich’s building, like the art of the Secession, makes no reference to the world of industry, machinery, or mass culture. Like Art Nouveau and Symbolism, to which it is connected, it is deeply escapist at its heart.

Even the Secession itself proved too restrictive, and in 1905 a group led by Klimt and including Moser and Hoffmann (the later two had formed the Wiener Werkstätte, or Viennese Workshops, in 1903) broke away, wishing to pursue a more complete intertwining of the visual and decorative arts. At the same, a group of women artists, such as Broncia Koller-Pinell and designer Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka (excluded from joining the all-male group), pursued parallel innovations and practices, forming a kind of “Female Secession” whose achievements have until recently largely been lost to history. Their multifaceted achievements in the fine and decorative arts are only now being recognized, changing our understanding of the wider artistic landscape in Vienna (Megan Brandow-Faller, The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy, Bloomsbury, 2020; Julie Johnson, The Memory Factory: The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900, Purdue University Press, 2012).

The currents of history

Both the Secession building and its exhibitions were under the control of the Nazi cultural offices after the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria into the Third Reich from 1938 to 1945). In February of 1945 an allied bomb landed squarely on the building, shattering the glass dome and destroying large parts of the structure. The current building is largely a reconstruction. Despite the Secessionists’ fervent desire for art to maintain its freedom, their works, like all art, can never be detached entirely from the larger currents of history.

Images

1. Josef Maria Olbrich, Secession Building, Vienna 1897–98

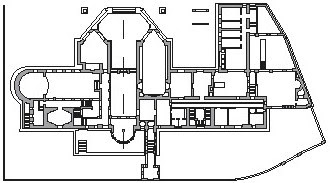

2. Joseph Maria Olbrich, elevation and plan for Secession parterre for Secession, 1898 (Secession Archive)

3. “Der Zeit ihre Kunst/Der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To Each Age its Art/To Art its Freedom)

4. Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze detail with “Ode to Joy,” 1901, casein, color, gold leaf, semi-precious stone, mother-of-pearl, plaster, charcoal and pencil on lime plaster, 215 x 481 cm (Secession Building, Vienna)

6. Gorgons, Josef Maria Olbrich, Secession Building, Vienna 1897–98

7. XIVth exhibition 1902, main hall with Beethoven statue by Max Klinger

8. Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, detail with “The longing for happiness finds its end in poetry,” 1901, casein, color, gold leaf, semi-precious stone, mother-of-pearl, plaster, charcoal and pencil on lime plaster, 215 x 516 cm (Secession Building, Vienna)

9. Kolomon Moser, Ver Sacrum cover, 1899

10. Gustav Klimt, Hope I, 1904, oil on canvas, 181 x 67 cm (National Gallery of Canada)

Source: Kahn Academy

Klimt's Beethoven Frieze and the 14th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession Chuck LaChiusa, “Architecture around the World: Secession Building,” European Architects and Artists on Buffalo Architecture and History, 2008 - BAH

Vienna Secession and the Secession Building

From the onset, the Vienna Secession brought together Naturalists, Modernists, Impressionists and cross-pollinated among all disciplines forming a total work of art; a Gesamkunstwerk. In this respect, the Secession drew inspiration from William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement which sought to re-unite fine and applied arts. Like Morris, the Secessionists spurned 19th century manufacturing techniques and favoured quality handmade objects, believing that a return to handwork could rescue society from the moral decay caused by industrialization.

Stylistically, the Secession has mistakenly been seen as synonymous with the Jugendstil movement, the German version of art nouveau. It is true that the Secessionists incorporated many of Jugendstil elements in its work such as the curvilinear lines that decorate the facade of the Secession building. Many of the organization’s members had been working in the Jugendstil style prior to joining and the group did honour the Art Nouveau movement in France by devoting an entire issue of Ver Sacrum in 1898 to the work Alphonse Mucha. Nevertheless, the Secession developed its own unique ‘Secession-stil’ centred around symmetry and repetition rather than natural forms.

The dominant form was the square and the recurring motifs were the grid and checkerboard. The influence came not so much from French and Belgian Art Nouveau, but again from the Arts and Crafts movement. In particular the work of William Asbhee and Charles Renee Mackintosh both of whom incorporated geometric design and floral-inspired decorative motifs, played a large part in forming the Secession-style. The Secessionist admiration of Mackintosh’s work was evident by the fact that he was brought to Vienna for the 8th Secession exhibition.

The influence of Japanese design cannot be understated in relation to the Secession. Japonism had swept through Europe at the end of the eighteenth century and French artists like Cezanne and Van Gogh; both of whom were avid collectors of woodblock prints were quick to incorporate elements in their work.

When Japonism arrived in Austria, the Viennese were also not immune to its influence. The Vienna International Exposition of 1873 featured a Japanese display complete with a shinto shrine and Japanese garden and hundreds of art objects. Japanese design was quickly incorporated by the Secessionists for its restrained use of decoration, its preference for natural materials over artifice, the preference for handwork over machine-made, and its balance of negative and positive space. In a way, the Secessionists saw in Japanese design their ideals of a ‘Gesamkunstwerk’, whereby design was seamlessly incorporated into everyday life. So strong were these ties that they devoted the Secession exhibit of 1903 to Japanese art.

From the onset, one of the most important aims of the secessionists was to have their own exhibition building. They had been required to rent for a considerable sum the building of the Horticultural Society for the first secession exhibition in March of 1898 and had seen the need to revise exhibition spaces from the traditional Salon model. Thanks to the financial success of this exhibition which drew some 57,000 visitors; including Emperor Franz Josef himself, they were able to undertake the construction of a permanent exhibition building. The location for this building; an area of roughly 1000 square meters on the corner of Karlsplatz just beneath the window of the Academy of Fine Arts and a short walk from the Ringstrasse, was both symbolic and controversial.

The architect chosen for the project was Josef Olbrich, a young pupil of Otto Wagner and one of only three architects (Josef Hoffmann, and Mayreder) who had joined the Secession. He had worked as a chief draugftsman for Wagner on the Stadtbahn during which time he was able to absorb Wagner’s trademark art nouveau ornamental details.

By the time Olbrich was designing the Secession building however, we see a drastic simplification of these Art Nouveau elements. Viewing Olbrich’s original sketches for the building, we can see a gradual reduction of decorative elements to basic geometric forms signifying a break from Wagner’s grandious art nouveau style.

Originally nicknamed ‘Mahdi’s Tomb’ or the ‘Assyrian convenience, it was not until the gold cuppola was in place that the most famous of nicknames was coined; ‘The golden cabbage.’

Like Klimt, Olbrich incorporated references to classical antiquity in the owl and gorgon (medussa heads) decorative motifs. Signifying the attributes of Athena; the goddess of wisdom and victory, Olbrich makes her both a liberator and guardian of the arts.

Excerpts source: Roberto Rosenman, "Vienna Secession: A History," pub. on Vienna Secession in 2015 (online)

More on the Secession Building

The large, white, cubic Secession Building was designed by architect Joseph Maria Olbrich in 1897 as the manifesto of the Secessionist movement. The exhibition hall opened in October 1898.

Most of the original interior was looted during World War II and the building was left in a desolate state until the passion for Viennese Art Nouveau was rediscovered in the 1970s and the pavilion rescued from decay.

The building is quite sober and only uses two colours, white and gold. Due to its massive, unbroken walls, the construction has the appearance of being constructed from a series of solid cubes. The most prominent feature of the otherwise clean design is the dome, made of 3,000 gilt laurel leaves. The laurel symbolizes victory, dignity and purity. Today the structure is one of the most treasured examples of a particularly Viennese artistic period.

Source: Secession Building (online Jan. 2017)

Ver sacrum: Mittheilungen der Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs

1) Universtaetsbibliothek Heidelberg: 1898, 1899, 1900, 1901, 1902, 1903

2) Feuilleton, by John Coulthart - 1898, 1899, 1900, 1901, Secession Posters

, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration #10: Turin and Vienna. Addenda: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Jugend Magazine, Jugend 1896, Jugend Magazine revisited, Simplicissimus, The Illustrator's Archive, Meggendorfer’s Blatter, Beardsley and Punch, Pan, Faun, G Archive, Kafka and Kupka

by Dr. Laura Morowitz

A New Freedom for Art

Imagine yourself walking down the street in Vienna and coming across the Secession Building. It’s oddness would likely stop you in your tracks. It certainly looks like nothing else around it—no school, no church, no government building. It’s gleaming white walls, lack of windows, gilded inscriptions and strange floating sphere of golden leaves looks like a temple built by some secretive, mythic people who long ago disappeared.

Architect Josef Maria Olbrich’s building perfectly expressed the aim of the group for whom it was built, the Vienna Secession: to set themselves apart, to shock and put forward a new form of beauty, something at once profoundly modern and as old as human nature. The Secession— a term meaning “to break away”—formed in April of 1897 when a number of members within the Association of Austrian Artists departed in frustration. These artists, architects, and designers had grown tired of nineteenth-century ideals and beliefs such as historicism (the constant reference to the past in art), positivism (a focus on that which can be rationally or scientifically proven), realism (a focus on art that creates an illusion of reality), and the commercialism of art (the idea that artists were working strictly for profit, rather than a more noble calling).

The Secession referred to the Union of Austrian Fine Artists (Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs). Painter Gustav Klimt was nominated as President and original members included architect Josef Hoffmann and designer Kolomon Moser. The central credo of the Secession was emblazoned in gold above the doorway: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst/Der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To Each Age its Art/To Art its Freedom). With this rallying cry the group made clear that it was the task of artists of each new generation to find their own language and subjects to express the moment in which they lived, rather than to constantly recycle the past. Throughout the nineteenth century, architects like Charles Garnier had created historicist buildings which drew upon both classical and baroque styles; the members of the Secession saw this as inherently dishonest. For them, art stood above politics, above commerce, and above ideology.

Exhibiting the New

Olbrich’s Secession building was the site for all the exhibitions of this group, beginning in October of 1898. Rather than nodding to periods or styles glorified in the nineteenth century, such as the High Renaissance or classicism, the building evokes other styles, including those of archaic Greece (as opposed to the art of the classical period) a style embraced in Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze in the interior) as well as other Mediterranean civilizations like ancient Egypt. The stretch of flat walls, made of plaster covered in whitewash, recalled the city walls and friezes of ancient Assyrian and Egyptian palaces and the strange proportions of Olbrich’s building include distant echoes of pylons (the gateway of ancient Egyptian temples). The forms of Western architecture—columns, arches, sloping roofs— are nowhere to be found.

Many commentators of the time found the open metal work sphere at the top, composed of 3,000 golden leaves, and recalling both laurel-leaf crowns and the thinly hammered gold jewelry of ancient Mediterranean, to be the strangest of all. The weirdness of the building earned it some memorable nicknames in its time including “Mahti’s tomb” and “The Golden Cabbage.” In addition to their rallying cry, the name of the group’s journal, Ver Sacrum (Sacred Spring), is written on the building.

Like the title, the three Greek gorgon masks that hover above the doorway evoke the world of archaic Greek art. The play of austerity against elements of decoration, like the stylized trees with gilded leaves is characteristic of the style of many artists within the early Secession, in media including architecture, ceramics, jewelry, painting and the graphic arts.

Inside the building, the innovative architecture continued. It was the first exhibition space designed with movable walls to accommodate different types of work. Beginning in 1898, the Secession held annual exhibits where the most innovative art, not only in Vienna, but throughout Europe, was put on display. It was one of the only spaces within Austria where artists could see a full range of the European avant garde including the work of artists like Honorary Secession members Fernand Khnopff, Edward Burne-Jones, and August Rodin. In addition to Klimt, Secession artists such as Hoffmann, Moser, and Otto Wagner would form the heart of Viennese Modernism in the arts and architecture. Perhaps the most famous of the Secession exhibits was the XIVth one, in 1902, devoted to the German composer Beethoven.

The entire building was turned over in tribute to him, with a sculpture by Max Klinger and Klimt’s enigmatic Beethoven Frieze painted around the upper walls of one gallery. The work was inspired by Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, played by Gustav Mahler at the opening of the exhibition, creating a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art—inspired by composer Richard Wagner’s concept where many art forms combine to express a unified vision.

A bridge between the old and the new

The work of the Secessionists was innovative and scandalous in its formal experimentation, for example in Moser’s woodcut for an 1899 cover of Ver Sacrum, with its non-naturalistic colors, flatness, surface design (as in the closely related Jugendstil), and simplified, bold drawing, at once elegant and powerful. It was also shocking in the way it dealt with new subjects and modern life in ways that were utterly shocking to the staid denizens of Viennese society; Gustav Klimt’s Hope I juxtaposed a nude, very pregnant woman with visible pubic hair, against symbols of death and decay. While some of the twentieth century’s greatest minds (including Sigmund Freud, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Arnold Schoenberg), were already at work in the city, Vienna was still the crown jewel of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had been ruled for decades by Emperor Franz Josef.

Writer Stephen Zweig captured the conservative nature of this culture when he noted that at twenty years, a man would know exactly what his life would be like at fifty. Into this stiff world of imperial pomp, elaborate waltzes and tight corsets, the members of the Secession displayed images of frank sexual desire, psychological fears, and morbid fantasies. For example, one of the most common motifs of Secession members was the femme fatale, the deadly seductive woman who reigns in the works of Klimt, Felicien Rops, Ferdinand Khnopff and others.

In many ways, the art produced during the early Secession, like Olbrich’s building, is a bridge between nineteenth-century Academic art and the abstraction that would come in the twentieth. Academic art refers to the manner and style taught in the European art academies of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, rooted in the classical art of Greece and Rome. Works produced in the academies were highly finished, naturalistic, and greatly idealized, like Frederic Leighton’s Bath of Psyche, painted for the British Royal Academy. The enticing, languid figures of the early Secession hark back to Academic ideals of beauty, but begin to abandon the traditional, illusionistic language passed down from the Renaissance.

The work of the Secessionists was often still tied to nineteenth-century ideas of beauty and sophistication, in contrast to the artistic movements that would emerge in the second decade of the twentieth century, like the Futurists or Die Brücke. For all its oddity, Olbrich’s building, like the art of the Secession, makes no reference to the world of industry, machinery, or mass culture. Like Art Nouveau and Symbolism, to which it is connected, it is deeply escapist at its heart.

Even the Secession itself proved too restrictive, and in 1905 a group led by Klimt and including Moser and Hoffmann (the later two had formed the Wiener Werkstätte, or Viennese Workshops, in 1903) broke away, wishing to pursue a more complete intertwining of the visual and decorative arts. At the same, a group of women artists, such as Broncia Koller-Pinell and designer Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka (excluded from joining the all-male group), pursued parallel innovations and practices, forming a kind of “Female Secession” whose achievements have until recently largely been lost to history. Their multifaceted achievements in the fine and decorative arts are only now being recognized, changing our understanding of the wider artistic landscape in Vienna (Megan Brandow-Faller, The Female Secession: Art and the Decorative at the Viennese Women’s Academy, Bloomsbury, 2020; Julie Johnson, The Memory Factory: The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900, Purdue University Press, 2012).

The currents of history

Both the Secession building and its exhibitions were under the control of the Nazi cultural offices after the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria into the Third Reich from 1938 to 1945). In February of 1945 an allied bomb landed squarely on the building, shattering the glass dome and destroying large parts of the structure. The current building is largely a reconstruction. Despite the Secessionists’ fervent desire for art to maintain its freedom, their works, like all art, can never be detached entirely from the larger currents of history.

Images

1. Josef Maria Olbrich, Secession Building, Vienna 1897–98

2. Joseph Maria Olbrich, elevation and plan for Secession parterre for Secession, 1898 (Secession Archive)

3. “Der Zeit ihre Kunst/Der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (To Each Age its Art/To Art its Freedom)

4. Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze detail with “Ode to Joy,” 1901, casein, color, gold leaf, semi-precious stone, mother-of-pearl, plaster, charcoal and pencil on lime plaster, 215 x 481 cm (Secession Building, Vienna)

6. Gorgons, Josef Maria Olbrich, Secession Building, Vienna 1897–98

7. XIVth exhibition 1902, main hall with Beethoven statue by Max Klinger

8. Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, detail with “The longing for happiness finds its end in poetry,” 1901, casein, color, gold leaf, semi-precious stone, mother-of-pearl, plaster, charcoal and pencil on lime plaster, 215 x 516 cm (Secession Building, Vienna)

9. Kolomon Moser, Ver Sacrum cover, 1899

10. Gustav Klimt, Hope I, 1904, oil on canvas, 181 x 67 cm (National Gallery of Canada)

Source: Kahn Academy

Klimt's Beethoven Frieze and the 14th Exhibition of the Vienna Secession Chuck LaChiusa, “Architecture around the World: Secession Building,” European Architects and Artists on Buffalo Architecture and History, 2008 - BAH

Vienna Secession and the Secession Building

From the onset, the Vienna Secession brought together Naturalists, Modernists, Impressionists and cross-pollinated among all disciplines forming a total work of art; a Gesamkunstwerk. In this respect, the Secession drew inspiration from William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement which sought to re-unite fine and applied arts. Like Morris, the Secessionists spurned 19th century manufacturing techniques and favoured quality handmade objects, believing that a return to handwork could rescue society from the moral decay caused by industrialization.

Stylistically, the Secession has mistakenly been seen as synonymous with the Jugendstil movement, the German version of art nouveau. It is true that the Secessionists incorporated many of Jugendstil elements in its work such as the curvilinear lines that decorate the facade of the Secession building. Many of the organization’s members had been working in the Jugendstil style prior to joining and the group did honour the Art Nouveau movement in France by devoting an entire issue of Ver Sacrum in 1898 to the work Alphonse Mucha. Nevertheless, the Secession developed its own unique ‘Secession-stil’ centred around symmetry and repetition rather than natural forms.

The dominant form was the square and the recurring motifs were the grid and checkerboard. The influence came not so much from French and Belgian Art Nouveau, but again from the Arts and Crafts movement. In particular the work of William Asbhee and Charles Renee Mackintosh both of whom incorporated geometric design and floral-inspired decorative motifs, played a large part in forming the Secession-style. The Secessionist admiration of Mackintosh’s work was evident by the fact that he was brought to Vienna for the 8th Secession exhibition.

The influence of Japanese design cannot be understated in relation to the Secession. Japonism had swept through Europe at the end of the eighteenth century and French artists like Cezanne and Van Gogh; both of whom were avid collectors of woodblock prints were quick to incorporate elements in their work.

When Japonism arrived in Austria, the Viennese were also not immune to its influence. The Vienna International Exposition of 1873 featured a Japanese display complete with a shinto shrine and Japanese garden and hundreds of art objects. Japanese design was quickly incorporated by the Secessionists for its restrained use of decoration, its preference for natural materials over artifice, the preference for handwork over machine-made, and its balance of negative and positive space. In a way, the Secessionists saw in Japanese design their ideals of a ‘Gesamkunstwerk’, whereby design was seamlessly incorporated into everyday life. So strong were these ties that they devoted the Secession exhibit of 1903 to Japanese art.

From the onset, one of the most important aims of the secessionists was to have their own exhibition building. They had been required to rent for a considerable sum the building of the Horticultural Society for the first secession exhibition in March of 1898 and had seen the need to revise exhibition spaces from the traditional Salon model. Thanks to the financial success of this exhibition which drew some 57,000 visitors; including Emperor Franz Josef himself, they were able to undertake the construction of a permanent exhibition building. The location for this building; an area of roughly 1000 square meters on the corner of Karlsplatz just beneath the window of the Academy of Fine Arts and a short walk from the Ringstrasse, was both symbolic and controversial.

The architect chosen for the project was Josef Olbrich, a young pupil of Otto Wagner and one of only three architects (Josef Hoffmann, and Mayreder) who had joined the Secession. He had worked as a chief draugftsman for Wagner on the Stadtbahn during which time he was able to absorb Wagner’s trademark art nouveau ornamental details.

By the time Olbrich was designing the Secession building however, we see a drastic simplification of these Art Nouveau elements. Viewing Olbrich’s original sketches for the building, we can see a gradual reduction of decorative elements to basic geometric forms signifying a break from Wagner’s grandious art nouveau style.

Originally nicknamed ‘Mahdi’s Tomb’ or the ‘Assyrian convenience, it was not until the gold cuppola was in place that the most famous of nicknames was coined; ‘The golden cabbage.’

Like Klimt, Olbrich incorporated references to classical antiquity in the owl and gorgon (medussa heads) decorative motifs. Signifying the attributes of Athena; the goddess of wisdom and victory, Olbrich makes her both a liberator and guardian of the arts.

Excerpts source: Roberto Rosenman, "Vienna Secession: A History," pub. on Vienna Secession in 2015 (online)

More on the Secession Building

The large, white, cubic Secession Building was designed by architect Joseph Maria Olbrich in 1897 as the manifesto of the Secessionist movement. The exhibition hall opened in October 1898.

Most of the original interior was looted during World War II and the building was left in a desolate state until the passion for Viennese Art Nouveau was rediscovered in the 1970s and the pavilion rescued from decay.

The building is quite sober and only uses two colours, white and gold. Due to its massive, unbroken walls, the construction has the appearance of being constructed from a series of solid cubes. The most prominent feature of the otherwise clean design is the dome, made of 3,000 gilt laurel leaves. The laurel symbolizes victory, dignity and purity. Today the structure is one of the most treasured examples of a particularly Viennese artistic period.

Source: Secession Building (online Jan. 2017)

Ver sacrum: Mittheilungen der Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs

1) Universtaetsbibliothek Heidelberg: 1898, 1899, 1900, 1901, 1902, 1903

2) Feuilleton, by John Coulthart - 1898, 1899, 1900, 1901, Secession Posters

, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration #10: Turin and Vienna. Addenda: Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, Jugend Magazine, Jugend 1896, Jugend Magazine revisited, Simplicissimus, The Illustrator's Archive, Meggendorfer’s Blatter, Beardsley and Punch, Pan, Faun, G Archive, Kafka and Kupka

Exposición de Joseph Maria Olbrich en el Museo Leopold de Viena

El arquitecto y diseñador Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867 – 1908) tuvo una gran importancia en el arte alrededor de 1900. Fue uno de los miembros fundadores de la Secesión de Viena, responsable de la construcción de la asociación de artistas y, como miembro de la colonia de artistas de Darmstadt, dio un impulso significativo a la escena artística alemana. De acuerdo con las ideas vanguardistas de su época, dedicó su obra a casi todos los ámbitos de la vida. Su espectro abarcó desde el diseño de casas e interiores, el diseño de telas, ilustraciones de libros y carteles, y hasta un modelo de automóvil para la empresa Opel. En los carteles de la segunda y tercera exposiciones de la Secesión, Olbrich estilizó la llamativa arquitectura del edificio, al cual presentó como una marca visual. Logró crear un gráfico elegante que, por su modernidad, anticipó los principios del diseño gráfico "objetivo" de la década de 1920 ya en 1898. También realizó dos carteles a la colonia de artistas de Darmstadt, que hoy se consideran entre los ejemplos más importantes del arte del afiche alemán.

El Museo Leopold en Viena muestra desde el 18.6. al 27 de septiembre de 2010 en cooperación con el Institut Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt y la Biblioteca de Arte – Museos Estatales de Berlín, la exposición más grande hasta la fecha sobre el trabajo de Joseph Maria Olbrich. Además de presentar la obra de vida del arquitecto, la muestra introduce el complejísimo desarrollo cultural de principios del siglo XX (Bernhard Denscher).

El arquitecto y diseñador Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867 – 1908) tuvo una gran importancia en el arte alrededor de 1900. Fue uno de los miembros fundadores de la Secesión de Viena, responsable de la construcción de la asociación de artistas y, como miembro de la colonia de artistas de Darmstadt, dio un impulso significativo a la escena artística alemana. De acuerdo con las ideas vanguardistas de su época, dedicó su obra a casi todos los ámbitos de la vida. Su espectro abarcó desde el diseño de casas e interiores, el diseño de telas, ilustraciones de libros y carteles, y hasta un modelo de automóvil para la empresa Opel. En los carteles de la segunda y tercera exposiciones de la Secesión, Olbrich estilizó la llamativa arquitectura del edificio, al cual presentó como una marca visual. Logró crear un gráfico elegante que, por su modernidad, anticipó los principios del diseño gráfico "objetivo" de la década de 1920 ya en 1898. También realizó dos carteles a la colonia de artistas de Darmstadt, que hoy se consideran entre los ejemplos más importantes del arte del afiche alemán.

El Museo Leopold en Viena muestra desde el 18.6. al 27 de septiembre de 2010 en cooperación con el Institut Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt y la Biblioteca de Arte – Museos Estatales de Berlín, la exposición más grande hasta la fecha sobre el trabajo de Joseph Maria Olbrich. Además de presentar la obra de vida del arquitecto, la muestra introduce el complejísimo desarrollo cultural de principios del siglo XX (Bernhard Denscher).