|

| Unprecedented: Abraham and the Idols |

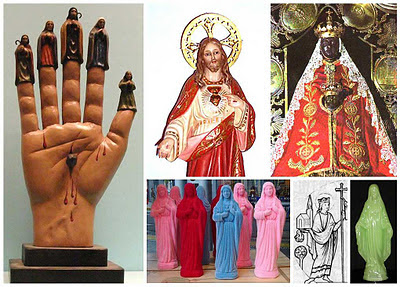

Aniconism is the practice or belief in avoiding or shunning images of divine beings, prophets or other respected religious figures, or in different manifestations, any human beings or living creatures. The term aniconic may be used to describe the absence of graphic representations in a particular belief system, regardless of whether an injunction against them exists.

The Second Commandment: "You shall not make unto you any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: 5 You shall not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me; 6 And showing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my Commandments." Exodus 20:4-6

Aniconism is a particular case of representation (the absence of images) and taboo (the prohibition of images). One of its aspects expresses the absence of images, while the other may contain an injunction conceived to regulate their absence. An avoidance and repugnance of representations is called

iconophobia. When unformalized predispositions or clearly stated legislations are put in practice and enforced, leading to the removal and destruction of representations, the aniconism becomes iconoclasm. Aniconism relates also to censorship, which takes place after a representation was already produced, but before, or shorthly after, it is made public, and also involves less violence than iconoclasm. In common usage, "aniconism" is used to designate the absence of paintings and statues, "taboo" characterizes behaviours, "censorship" is applied to written materials and "iconoclasm" to the destruction of paintings and statues.

Aniconism is a gradual phenomenon, having appeared at various times in many cultures across the world and within the same culture during its history. It is usually restricted to specific circumstances of space, time, object or modality. The intensity of aniconism is characterized by periodicity.

The fundamental cause of aniconism is embedded in the problematic nature of representation itself. There is an unavoidable need to represent the world since this is how our cognition works. But what is the validity of a representation not perceptible to our biological senses of something outside their reach or immaterial--God, time, ultraviolet? Furthermore, how to present a general model by a specific occurrence? Everybody knows what a human looks like, but everyone will draw him or her in a different way. Because these are inherent and not transitory problems, they generate a perpetual search for solutions, making of aniconism a continuously fluctuating phenomenon.

Aniconism is best known in connection to Abrahamic religions. In monotheism, aniconism was shaped by specific theological considerations and historical contexts. It emerged as a corollary of seeing God's position as the ultimate power holder, and the need to defend this unique status against competing external and internal forces, such as pagan idols, critical humans, and mass society. Idolatry is a threat to uniqueness, and one way that prophets chose to fight it was through the prohibition of material representations. The same solution also worked against the pretension of humans to have the same power of creation as God (hence their banishment from the Heavens, the destruction of Babel, and the Second Commandment in the biblical texts, or the myth of the golem in Jewish literature).

Religious art and art with religious references make a substantial part of humanity's artistic production. As such, religious aniconism is in fact much about art. While not usually classified as aniconism, it occurs frequently in profane art, as a quantitative characteristic of amount of details present in objects. Extremes can range for example between the 18th century Rococo and the 20th century Minimalist art.

Working on various cultures, a group of modern scholars has gathered material showing that in some cases the idea of aniconism in religion may be an intellectual construction suiting specific intents and historical contexts.

In Africa, aniconism varies from culture to culture from elaborate masks and statues of humans and animals to their total absence. Yet, a common feature across the continent is that the "High God" is never given material shape. On the Germanic tribes, the Roman historian Tacitus writes that "They don't consider it mighty enough for the Heavens to depict Gods on walls or to display them in some human shape" (Publius Cornelius Tacitus, "9. Götterverehrung",

Germania: De origine et situ Germanorum liber, Stuttgart: Reclam, 2000). But his observation is not a general rule: consider, for instance,

Ardre image stones.

|

| Abraham smashing the idols, 17th Century BCE |

Abraham and the idols. According to Hebrew oral tradition and the

Midrash (Midrash Bereishit Rabbah 38:13),[2] when Abraham was still a young child, he realized that idol worship was nothing but foolishness. One day, when Abraham was asked to watch his father's idol store. Abraham would call to the passersby, "Who’ll buy my idols? They won’t help you and they can’t hurt you! Who’ll buy my idols?" And when people came in and wanted to buy idols, Abraham asked, "How old are you?" The person said, "Sixty". Abraham responded, "Isn't it pathetic that a man of sixty wants to bow down to a one-day-old idol?" Then the man felt ashamed and left. Later, Abraham took a hammer and smashed all the idols - except for the largest. When his father came back and saw the broken idols, he was appalled. "Who did this?" he cried. And Abraham replied calmly: "It was amazing, Dad, the idols all got into a fight and the biggest idol won!" Rabbi Shraga Simmons explains that Abraham's idea was to show his father how ridiculous was to ascribe power to such idols. Indeed, there was no way for his father to respond; deep down he knew that Abraham had tuned into a deeper truth.[3] Significantly, the account of Abraham and idols can also be found in the Qur'an 21:51-70.[4]

Questions

A. Was the significance of Abraham being an idol smasher to challenge a tradition? Which?

B. Was Abraham right in smashing the idols? Why?

C. Do you challenge traditions?

D. Are people willing to challenge their own traditions? Or, do they mostly complain about other people's traditions and think their own are fine?

E. In what ways do you question tradition and in what areas are you less likely to question tradition?

Notes

1. For a debate, see

What's so terrible about idolatry?,

The purpose and meaning of the Second Commandment

2.

Azamra

3. Shraga Simmons,

Abraham breaking idols,

Ask the Rabbi in

About.com

4. M.S.M. Saifullah,

The Story of Abraham and [the] Idols in the Qur'an and Midrash Genesis Rabbah,

Islamic Awareness, 2002-6; see also

the additional comments.

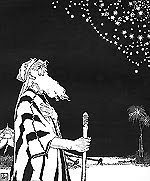

Nimord's kingdom is about to face its greatest challenger in a young boy named Abraham. While little is known of Abraham's childhood in the Torah, the Midrash presents a mighty tale of this courageous boy who stands toe to toe against the most powerful ruler of the ancient world. Young Abraham, Montreal: Big Bang Digital Studios, 2011; Chabad.

On the night Abram is born, King Nimrod’s chief stargazer witnesses a cosmological phenomenon in the sky: one small star consumes four larger stars. The rays of this star shine down upon the house of the King’s general, Terakh, whose wife had just given birth to a baby boy named Abram. The prophecy discerned by the astrologer warns that his child will go against the gods and Nimrod’s mighty kingdom. Nimrod demands Terakh hand over his son. Terakh agrees, but deceives Nimrod by giving him a baby boy, born to a servant girl, while Amaslai flees with Abram to hide him in the wilderness.

Abram lives in the wilderness for 13 years and comes to believe in the one true Creator God. Knowing that his understanding is limited, Abram begins a journey to find a wise man who can teach him about God. So he returns to his family in Ur Chasdim, the seat of Nimrod’s kingdom.

Abram comes face to face with the foolishness of idolatry. As a 13 year old, he does his best to combat idolatry but finds himself in big trouble after destroying all the idols in the family’s idol shop. General Terakh hands his son over to the kings soldiers for arrest and certain death. Yet God intervenes and Abram miraculously escapes the city unharmed.

Abram continues his search for a wise man who can teach him about God and finds the wise Noach in the land of Canaan, who teaches him the ways of God. But Abram is not to remain in Canaan. The wickedness of the land cries out for God’s judgment as it did before the flood. Noach sends Abram back to Ur to challenge Nimrod and abolish idolatry before God’s patience is exhausted again.

Midrashic sources

A. Terach leaves idol shop and Avram had to take over. "The bigger the idol the higher the price!" –

Midrash HaGadol Bereishis 11:28

B. Avram hit a hammer on idols heads. "Do you want this one or that one?" –

Midrash HaGadol Bereishis 12:1

C. "I’m 60 and I want an idol!" "You want a one-day old idol?" –

Bereishis Rabbah 38:8 (19)

D. "Thieves stole my idol!" "Can’t your idol protect itself?" The guy serves G-d after Avram says the thieves will return your things to you and they are returned. He tells many people what Avram did, and Nimrod has him killed –

Bereishis Rabbah 38:19,

Beis HaMidrash Cheder 1

E. Avram broke all the idols and placed a hammer in the biggest ones hand. Conversation with Terach –

Bereishis Rabbah 38:8 (19),

Midrash HaGadol Bereishis, SH

___________________________________________________

Aspectos do aniconismo identitário. Ivan Esperança Rocha,

Imagem no judaísmo: aspectos do aniconismo identitário (Image in Judaism: Aspects of Indentity Aniconism),

História, São Paulo, vol. 26, no. 1, 2007

A imagem tem recebido uma crescente atenção no âmbito das ciências sociais e humanas, particularmente no campo da historiografia, o que se depreende de inúmeros eventos e publicações nivelem âmbito nacional e internacional. As imagens, ou fontes visuais, começam a ser tratadas como uma importante evidência histórica, e igualadas em valor à literatura e documentos de arquivos.1 Em vez de seu valor afetivo e subjetivo que tinha caracterizado a Antiguidade e a Idade Média, buscam-se agora conhecimentos mais sistemáticos e consistentes sobre elas. Demonstra-se que os fatos sociais se refletem em mecanismos visuais.2

A cerâmica, manuscritos com pinturas, imagens soltas de propaganda política e religiosa, quadros, estátuas, fotografias ou simplesmente material visual ganham uma importância não mais apenas ligada às suas qualidades estéticas mas à sua capacidade de representar os imaginários sociais e de evidenciar as mentalidades coletivas.3 "No estudo das sociedades antigas, a iconografia, neste seu significado mais amplo de material visual, assume um papel de destaque, particularmente, quando não se tem a contrapartida da documentação escrita ou quando esta é lacônica", como se verifica na iconografia funerária ou templária do Egito.4

Por outro lado, na cultura judaica, bem próxima do Egito, no espaço e no tempo, o acesso a dados provenientes da iconografia é muito limitado.5

Os judeus consideraram sua religião e seu código religioso de comportamento um elemento essencial de sua identidade e de sua sobrevivência ante os inúmeros momentos de dispersão em que foi envolvido. Entre as leis do corpo normativo israelita se encontra uma proibição de produzir ou conservar imagens com o intuito de preservar uma idéia de monoteísmo, que iria de certa forma represar a arte israelita durante séculos. A proibição, inicialmente ligada à reprodução de ídolos estrangeiros, acaba se estendendo a outros tipos de representação iconográfica, particularmente ligada à figura humana – considera-se o homem criado à imagem de Deus, que vigorou, com uma certa intensidade, praticamente até as portas da Haskalah, o iluminismo judaico, iniciado em fins do século XVIII.

A normalização da proibição de imagens em Israel encontra-se no livro do Êxodo: "Não farás para ti imagem de escultura, nem semelhança alguma do que há em cima, nos céus, nem embaixo, na terra, nem nas águas debaixo da terra" (20,4). Esta proibição faz parte da legislação religiosa de Moisés e pode ser entendida, dentre outros textos, por meio de Isaías: "A quem havereis de comparar a Deus? Que semelhança podereis produzir dele?" (40,18).

Em um ambiente permeado por cultos idolátricos (Ex 20,5; 34,15, Sl 44,21, 1 Rs 11,8ss, 19,18, Jr 7,18, Is 10,10), os judeus querem se distinguir pela ausência de imagens de Javé. Assim, com raras exceções, com veremos mais adiante, fica proibida a produção de efígies da divindade israelita.6 Isso, no entanto, não vai banir a presença de imagens. Uma das estratégias nesse sentido será a utilizada por Salomão que passa a contratar artistas externos à comunidade israelita para a construção e embelezamento do Templo de Jerusalém, como é o caso de Hiram, um artista de Tiro que tinha grande habilidade no trabalho com bronze (1 Rs 7,13-14). Entende-se, assim, que a proibição não atingia os artistas estrangeiros e dessa maneira se pode justificar a presença de figuras de querubins e leões nos painéis do Templo (1 Rs 7,26).

Uma outra razão da presença de imagens entre os judeus envolvia o casamento dos reis israelitas com estrangeiras que traziam consigo seus cultos e seus deuses.7 De fato, as descobertas arqueológicas trouxeram à tona uma série de iconografias do período bíblico, como sinetes com figuras de animais, plantas e outros objetos e figuras em argila de nus femininos, estas muito comuns em Jerusalém.

Sinagogas do período próximo à destruição do Templo, em 70 d.C., possuem decorações com figuras geométricas e de plantas; entre os judeus que participaram da revolta de Bar-Kokhba contra os romanos, em 135 d.C., foram encontrados vasos decorados com faces humanas; mas para que se evitasse seu uso como objetos idolátricos os olhos foram apagados.8

No entanto, mesmo com relação à proibição da representação de Javé, existem exceções, como se verifica numa fortaleza, em Kuntillet 'Ajrud, na Península do Sinai, onde foram encontrados graffiti com imagens de Iahweh ao lado de sua Ashera.9

|

Fragmento de cerâmica

Kuntillet Ajrud, sul do Negev, séc. [IX-]VIII a.C. |

Pode-se dizer que os judeus foram mais tolerantes com imagens que não tivessem relações com o culto. Com o declínio do politeísmo helênico-romano, muitas sinagogas começam a usar motivos da iconografia pagã, adaptando-as às suas necessidades, assim como cenas bíblicas como as da sinagoga de Dura-Europos nas proximidades do rio Eufrates.10

No século VII, com a conquista do Oriente pelo Islamismo anicônico, os judeus voltam a abandonar as imagens, adaptando-se à nova situação. As constantes dificuldades postas pelo segundo mandamento podem ser vislumbradas no manuscrito judaico ilustrado, chamado Haggadah da Cabeça de Ave. O texto narra a história do êxodo do Egito, onde todas as figuras humanas são representadas por cabeças de pássaros para evitar a proibição icônica.

A discussão sobre a questão da imagem do Antigo Testamento é retomada no Talmude, uma compilação e adaptação de leis e tradições judaicas, realizadas entre 200 a.C. e 500 d.C., que consistem em 63 tratados de assuntos legais, éticos e históricos. O judaísmo ortodoxo baseia suas leis no texto do Talmude. Tem entre seus tratados um específico sobre imagens e ídolos, o 'Abodah Zarah.

De um lado, este tratado expressa uma rígida oposição aos ídolos, proibindo não apenas sua fabricação, mas até mesmo olhar e pensar neles (Tosefta, Shabbath 17,1 et passim; Berakhot 12b). Os ídolos não deviam ser apenas quebrados, mas jogados no Mar Morto para que não pudessem ser mais vistos ('Abodah Zarah 3,3). A madeira de uma asherah não podia ser usada nem para aquecer-se (Pesahim, 25a). Para evitar qualquer contato com os idólatras, os judeus não podiam relacionar-se comercialmente com eles pelo menos três dias antes de suas festas cultuais ('Abodah Zarah 1,1). Ficava proibido caminhar sobre uma rua pavimentada com pedras que tinham sido utilizadas para construir o pedestal de um ídolo ('Abodah Zarah 50a). Aos sábados era proibido até mesmo ler o que estava escrito sob uma pintura ou estátua ('Abodah Zarah 149).

Por outro lado, encontramos no Talmude posições mais abertas com relação às imagens. Não se proíbe qualquer imagem, mas apenas aquelas que tenham um cunho cultual. Estátuas de reis, em um ambiente em que não são consideradas objeto de culto, não são proibidas ('Abodah Zarah 40a). Imagens para ornamentação são permitidas. Qualquer figura dos planetas é permitida, com exceção do sol e da lua (quase sempre representados com cunho cultual) ('Abodah Zarah 43b). Uma asherah é uma árvore sob a qual se pratica um culto e, portanto, proibida. Se, no entanto, existir um altar de pedras sob ela, a árvore pode ser utilizada livremente ('Abodah Zarah 48a).

A ambigüidade do tratamento dado às imagens começa a declinar com a Haskalah, um movimento entre judeus europeus do séc. XVIII, conhecido como o iluminismo judaico, calcado nos valores iluministas, que buscou promover maior integração com a sociedade européia, ampliando o espaço da educação secular e definindo os rumos de um movimento político pela emancipação judaica.11

O movimento encontrou inicialmente oposição entre os judeus ortodoxos por julgarem que a Haskalah contrariava os princípios do judaísmo tradicional, mas não deixou de ter adeptos entre eles. Uma das idéias contrapostas pela Haskalah é a do messianismo, como a espera de um gesto miraculoso em favor dos judeus; o exílio judaico também deixa de ser interpretado como uma vontade divina, mas como resultado de fatores históricos.12 Outra influência foi nas artes, com uma ampla revisão de proibições tradicionais, particularmente no que se refere à proibição de imagens.

Como reflexo desse movimento, nos séculos XIX e XX vimos o surgimento de grandes artistas judeus como Marc Chagall (1887-1985) com seus esplêndidos vitrais das doze tribos judaicas conservados na Sinagoga do Hospital Hadassa de Jerusalém, e Lasar Segall, um judeu lituano radicado no Brasil que transformou sua casa em museu com um acervo em torno de 2.500 obras.

Deve-se dizer, no entanto, que a Haskalah, do ponto de vista artístico, foi precedida pela ação de judeus, que apesar de não se envolverem com a pintura já tinham se dedicado a outros tipos de expressões artísticas, como a joalheria, cunhagem de moedas e medalhas, ourivesaria, gravação em madeira, cerâmica, caligrafia e ilustração de manuscritos hebraicos, dentre outras.13

Numa exposição realizada no Museu Judaico de Nova York, de 18 de novembro de 2001 a 17 de março de 2003, foi apresentada e discutida a arte desenvolvida durante o processo de aculturação judaica no século XIX, sendo apresentada como uma das conseqüências da Haskalah.

Por fim, os judeus, ao se perguntarem se suas antigas leis ainda têm algum valor na atualidade, particularmente, se a proibição de imagens como objeto de culto ainda tem algum valor para a sociedade moderna, encontram uma resposta nas palavras de uma exegeta judia, Nechama Leibowitz (1905-1997), para quem o segundo mandamento ainda continua válido, dado que objetos e bens de materiais, ou a própria ciência, são guindados a uma posição de culto no mundo moderno.14

Notas

1 BURKE, Peter. "O testemunho das imagens,"

Testemunho ocular: História e imagem, Bauru: Edusc, 2004, p.15

2 MENESES, Ulpiano T. Bezerra de. "Fontes visuais, cultura visual, História visual: balanço provisório, propostas cautelares,"

Revista Brasileira História, v. 23, n. 45, 2003, p. 11ss.

3 CHARTIER, R. Imagens, in: BURGUIÈRE, A.,

Dicionário das Ciências Históricas, trad. Jayme Salomão, Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1993, pp. 406-7

4 ROCHA, Ivan Esperança.

Práticas e representações judaico-cristãs, Assis: FCL–Assis–Unesp Publicações, 2004, p. 29

5 LIVERANI, Mario.

Antico Oriente: Storia, Società, Economia, Bari: Laterza, 2005, p.688-89

6 RAD, G. Eikôn von. In:

Grande Lessico del Nuovo Testamento, ed. G. Kittel, Brescia: Paideia, 1967, v. 3, col. 143

7 EHRLICH, Car. Make Yourself No Graven Image: The Second Commandment and Judaism. In:

Thirty Years of Judaic Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Amherst, 2004, pp. 254-71

8 YADIN, Yigael.

Bar-Kokhba: The Rediscovery of the Legendary Hero of the Last Jewish Revolt against Imperial Rome, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971, p. 86-111 (Ehrlich, p. 261)

9 DEVER, William G. "Asherah, consort of Yahweh? New evidence from Kuntillet Ajrud,"

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 255, 1984, p. 21ss

10 KRAELING, Carl H. "The Excavations at Dura-Europos Final Report 8/1,"

The Synagogue, New Haven: Yale University, 1956 (Ehrlich, p. 262ss

11 ROSENTHAL, Herman Peter. "Haskalah,"

The Jewish Encyclopedia, New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1901-1906, v. 8, p. 256-58

12 SHOENBERG, Shira.

The Haskalah,

Jewish Virtual Library (acesso 10.9.2006)

13 PASTERNAK, Velvel.

Music and Art,

Judaism.com (acesso 10.9.2006)

14 GROSSBARD, Sylvie.

Shemot–Yitro,

USY (acesso 3.11.2006).