|

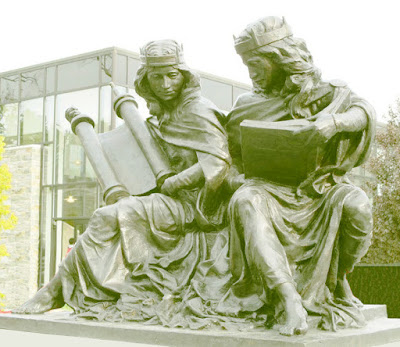

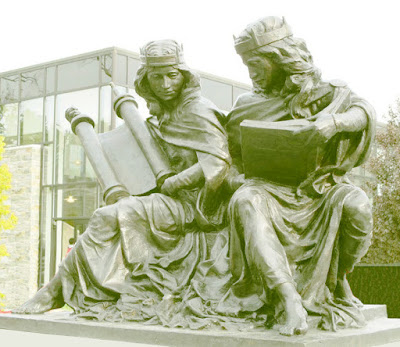

| Joshua Koffman, Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time, maquette, April 2015 |

1. SJU Announces Details of Sculpture to Mark 50 Years of New Catholic-Jewish Relationship, SJU, Philadelphia, 24.4.2015

PHILADELPHIA (April 24) – Saint Joseph’s University has formally commissioned local artist Joshua Koffman to craft an original sculpture entitled, “Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time.” To be situated prominently on the campus near the Chapel of Saint Joseph–Michael J. Smith, S.J. Memorial, Koffman’s preliminary design has been completed and work on the final statue has begun.

The sculpture is part of the University's celebration with the Philadelphia Jewish community of the 50th anniversary of the Second Vatican Council declaration, Nostra Aetate (Latin for its opening words, “In Our Time”). That 1965 statement repudiated centuries of Christian claims that Jews were blind enemies of God whose spiritual life was obsolete. The document called instead for friendship and dialogue between Catholics and Jews. Shortly after, what was then Saint Joseph’s College became the first American Catholic college to respond to this appeal by establishing the Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations. The sculpture will also memorialize the Institute’s work and mission.

On numerous medieval cathedrals statues of the female allegorical figures of Church (Ecclesia) and Synagogue (Synagoga) portrayed the triumph of Christianity over Judaism. Ecclesia is crowned, majestic and victorious. Synagoga is defeated and blindfolded, her crown fallen at her feet.

"In 1965, Nostra Aetate rejected such images, declaring that Jews are beloved by an ever-faithful God whose promises are irrevocable," says University President, C. Kevin Gillespie, S.J. ’72. "The statue of 'Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time' will portray Jews and Christians using the medieval figures in a strikingly different way to express Catholic teaching today."

According to Institute Director Philip A. Cunningham, Ph.D., the new sculpture will employ Synagoga and Ecclesia rendered with nobility and grace, to bring to life the words of Pope Francis: “Dialogue and friendship with the Jewish people are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. There exists between us a rich complementarity that allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another mine the riches of God’s word.” The work will depict the figures enjoying studying each other’s sacred texts together.

“The sculpture will vividly convey what Pope Francis has called the ‘journey of friendship’ that Jews and Catholics have experienced in the past five decades,” observes Jewish Studies professor and Institute Assistant Director, Adam Gregerman, Ph.D. “We are looking forward to area Jews and Catholics coming together to celebrate the remarkable rapprochement that is occurring.”

Artist Joshua Koffman is a Philadelphia-based sculptor known for his expressive and dramatic large-scale bronze sculptures. The recipient of many distinguished awards including the Alex J. Ettl Grant, the John Cavanaugh Memorial Prize, and First Place in the Grand Central Academy’s Sculpture Competition, he pursued formal art education at the University of California, Santa Cruz and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he currently teaches.

“I am certainly looking forward to creating a sculpture that will communicate an incredibly unique and important message that will be central to such an extraordinary occasion as this historic anniversary,” Koffman says.

2. The Medieval Motif of Synagoga and Ecclesia and Its Transformation in a Post-Nostra Aetate Church, SJU, April 2015

In the Middle Ages, the feminine figures of Ecclesia (Church) and Synagoga (Synagogue) were a familiar motif in Christian art. It was a visual presentation of the understanding of the relationship between Christianity and Judaism that prevailed in that era. Mary C. Boys has described it as follows:

We can see a [particular] pattern in the Christian iconography of the dual figures Synagoga and Ecclesia. For many Christians of the Middle Ages, the status of Judaism evoked images from Lamentations (1:1; 5:16-17):

PHILADELPHIA (April 24) – Saint Joseph’s University has formally commissioned local artist Joshua Koffman to craft an original sculpture entitled, “Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time.” To be situated prominently on the campus near the Chapel of Saint Joseph–Michael J. Smith, S.J. Memorial, Koffman’s preliminary design has been completed and work on the final statue has begun.

The sculpture is part of the University's celebration with the Philadelphia Jewish community of the 50th anniversary of the Second Vatican Council declaration, Nostra Aetate (Latin for its opening words, “In Our Time”). That 1965 statement repudiated centuries of Christian claims that Jews were blind enemies of God whose spiritual life was obsolete. The document called instead for friendship and dialogue between Catholics and Jews. Shortly after, what was then Saint Joseph’s College became the first American Catholic college to respond to this appeal by establishing the Institute for Jewish-Catholic Relations. The sculpture will also memorialize the Institute’s work and mission.

On numerous medieval cathedrals statues of the female allegorical figures of Church (Ecclesia) and Synagogue (Synagoga) portrayed the triumph of Christianity over Judaism. Ecclesia is crowned, majestic and victorious. Synagoga is defeated and blindfolded, her crown fallen at her feet.

"In 1965, Nostra Aetate rejected such images, declaring that Jews are beloved by an ever-faithful God whose promises are irrevocable," says University President, C. Kevin Gillespie, S.J. ’72. "The statue of 'Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time' will portray Jews and Christians using the medieval figures in a strikingly different way to express Catholic teaching today."

According to Institute Director Philip A. Cunningham, Ph.D., the new sculpture will employ Synagoga and Ecclesia rendered with nobility and grace, to bring to life the words of Pope Francis: “Dialogue and friendship with the Jewish people are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. There exists between us a rich complementarity that allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another mine the riches of God’s word.” The work will depict the figures enjoying studying each other’s sacred texts together.

“The sculpture will vividly convey what Pope Francis has called the ‘journey of friendship’ that Jews and Catholics have experienced in the past five decades,” observes Jewish Studies professor and Institute Assistant Director, Adam Gregerman, Ph.D. “We are looking forward to area Jews and Catholics coming together to celebrate the remarkable rapprochement that is occurring.”

Artist Joshua Koffman is a Philadelphia-based sculptor known for his expressive and dramatic large-scale bronze sculptures. The recipient of many distinguished awards including the Alex J. Ettl Grant, the John Cavanaugh Memorial Prize, and First Place in the Grand Central Academy’s Sculpture Competition, he pursued formal art education at the University of California, Santa Cruz and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he currently teaches.

“I am certainly looking forward to creating a sculpture that will communicate an incredibly unique and important message that will be central to such an extraordinary occasion as this historic anniversary,” Koffman says.

2. The Medieval Motif of Synagoga and Ecclesia and Its Transformation in a Post-Nostra Aetate Church, SJU, April 2015

In the Middle Ages, the feminine figures of Ecclesia (Church) and Synagoga (Synagogue) were a familiar motif in Christian art. It was a visual presentation of the understanding of the relationship between Christianity and Judaism that prevailed in that era. Mary C. Boys has described it as follows:

We can see a [particular] pattern in the Christian iconography of the dual figures Synagoga and Ecclesia. For many Christians of the Middle Ages, the status of Judaism evoked images from Lamentations (1:1; 5:16-17):

How lonely sits the city

that once was full of people!

How like a widow she has become,

she that was great among the nations!

She that was a princess among the provinces

has become a vassal.

The crown has fallen from our head;

woe to us, for we have sinned!

Because of this our hearts are sick,

because of these things our eyes have grown dim.

Like Leah of the weak eyes (see Genesis 29:17), Synagoga was blind to Christ. As second-century apologist Justin Martyr said to the Jew Trypho, "Leah is your people and the synagogue, while Rachel is our church ...; Leah has weak eyes, and the eyes of your spirit are also weak." Synagoga symbolizes an obsolete Judaism.

In some depictions of this allegorical pair, we see a triumphant Ecclesia standing erect next to the bowed, blindfolded figure of the defeated yet dignified Synagoga (e.g., the thirteenth-century stone figures in the cathedrals of Strasbourg, Freiburg, Bamberg, Magdeburg, Reims, and Notre Dame [Paris]). Though the church has triumphed over synagogue, the latter is a tragic rather than sinister figure--a woman conquered, with her crown fallen, staff broken, and Torah dropping to the ground. ...

Other representations of Synagoga, particularly in the Late Middle Ages, present a more contemptible figure. For example, in a fifteenth-century portrayal of the crucifixion, Ecclesia holds a chalice to receive the blood from the pierced heart of Jesus, whereas Synagoga turns away from him, in the clasp of a devil who rides atop her neck and blinds her to the Christ by covering her eyes. The association with the devil evokes a malevolent Synagoga. ... Many [Medieval Christians] would have viewed the figures of Synagoga and Ecclesia, and thereby absorbed a dangerous lesson: Judaism no longer has reason to exist (Mary C. Boys, Has God Only One Blessing? - Judaism as a Source of Christian Self-Understanding, Paulist Press, 2000, 31-35).

Contrast this long-lived derogatory Christian attitude toward Judaism with these recent words of Pope Francis:

We hold the Jewish people in special regard because their covenant with God has never been revoked, for “the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable” (Rom 11:29). ... Dialogue and friendship with the children of Israel are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. The friendship which has grown between us makes us bitterly and sincerely regret the terrible persecutions which they have endured, and continue to endure, especially those that have involved Christians. God continues to work among the people of the Old Covenant and to bring forth treasures of wisdom which flow from their encounter with his word. For this reason, the Church also is enriched when she receives the values of Judaism (Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, 2014, 247-249).

Clearly Catholic attitudes have changed. A new relationship of respect has replaced the previous one of disdain. The turning point was the Second Vatican Council declaration, Nostra Aetate, issued on October 28, 1965.

The statue being prepared for Saint Joseph's University to mark the declaration's 50th anniversary will reinterpret the medieval motif of Synagoga and Ecclesia to reflect the teaching of the Catholic Church today. "Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time" will depict Synaogue and Church as both proud crowned women, living in covenant with God side by side, and learning from one another’s sacred texts and traditions about their distinctive experiences of the Holy One.

3. Sculpting a New Tradition: From Adversaries to Two Peoples in Covenant to Study Partners, SJU, April-July 2015

In Medieval Europe, the feminine figures of victorious Church (Ecclesia) and vanquished Synagogue (Synagoga) adorned dozens of cathedrals and churches. A famous depiction at the Cathedral of Strasbourg (ca. 1230) shows regal Church wearing a crown and bearing a cross-topped staff of authority and the chalice of the Eucharist. To the right, Synagogue is slumped and blindfolded, her crown has fallen to her feet, her staff is broken, and a tattered scroll of the Torah seems about to fall from her hand. Ill. Strasbourg

The figures also were regularly portrayed on either side of the crucified Jesus. Here in an early 15th century German Bible history book, Church collects the precious blood of Jesus into her chalice. Synagogue's vision is blocked by a demon on her head, who also casts off her crown.

When Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned King of Italy at the Cathedral of Milan on May 26, 1805, he ordered that work to complete its façade should begin at once. Seven years later, the traditional images of Synagogue and Church were transformed into somewhat secularized figures to show the legal equality of all religions in the Napoleonic state. Church is the Lady of Liberty of Enlightenment-era political thought, while Synagogue displays the universal philosophy of the Ten Commandments. Ill. Milan statues

In the first decades of the 20th century, the American artist John Singer Sargent reprised the medieval images of Synagogue and Church in paintings for the Boston Public Library. As in the older portrayals, she has lost her crown, her staff is broken, and her eyes are blindfolded. Although she retained some dignity in many medieval depictions, here she is thoroughly desolate. Such demeaning images contradict Catholic teaching since the Second Vatican Council's 1965 declaration Nostra Aetate. Ill. John Singer Sargent, Synagogue

For her book, Has God Only One Blessing? Judaism as a Source of Christian Self-Understanding (Paulist Press, 2000), Mary C. Boys commissioned Paula Mary Turnbull, a member of her religious community, to prepare small brass statues of Synagoga and Ecclesia as both in covenant with God. This idea of reimagining the negative medieval motif to reflect Catholic teaching since Nostra Aetate inspired the SJU sculpture to mark the declaration's 50th anniversary: "Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time." Ill. Paula Turnbull statuettes

With this basic premise, a number of artists were invited to submit concept sketches. One of Joshua Koffman's earliest clay drafts appealingly showed Church and Synagogue as comfortable being with and interacting with each other.

This interactive dynamic recalled the words of Pope Benedict XVI in 2011: "After centuries of antagonism, we now see it as our task to bring these two ways of rereading the biblical texts—the Christian way and the Jewish way—into dialogue with one another, if we are to understand God's will and his word aright." This led to the concept of portraying Synagogue and Church as sharing their respective sacred texts with each other, crudely suggested by inserting clip art texts to show them learning together.

Joshua Koffman took this basic concept and significantly developed it in another rough clay sketch. Besides having them holding their sacred texts, he added simple crowns to both figures, using that medieval symbol to indicate that both Synagogue and Church experience covenantal life with God.

In the final clay sketch before doing drapery studies for the Artist's Model, Joshua Koffman refined the Torah scroll and Christian Bible and how they are grasped. The image of Synagogue and Church reading together evokes the traditional Jewish chavruta method of studying the Talmud in pairs.

After doing drapery studies with live models, the larger Artist's Model is completed. The Torah scroll and Christian Bible are more substantial and are held in complementary ways. As Pope Francis has written: "God continues to work among the people of the Old Covenant and to bring forth treasures of wisdom which flow from their encounter with his word. For this reason ... there exists as well a rich complementarity [between us] which allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another to mine the riches of God’s word" [Evangelii Gaudium, 249].

4. Murray Watson, ICCJ concludes Annual Meeting in Rome, CCJR, 1.7.2015

(ROME) In a historic gathering in the Vatican on June 30, Pope Francis welcomed more than 250 Jewish and Christian leaders from the International Council of Christians and Jews. The Pope met with them to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the ground-breaking Vatican II declaration “Nostra Aetate,” which opened up new horizons in the Catholic Church’s approach to interfaith relations. [...]

The new statue of Ecclesia and Synagoga (Church and Synagogue) has been commissioned by Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia to honour the Nostra Aetate anniversary.

In contrast to the many portrayals of Ecclesia and Synagoga found in medieval cathedrals and manuscripts (which generally portrayed Ecclesia as triumphant, and Synagoga as defeated), this modern work of art depicts the two figures as equal in dignity and beauty, looking with curiosity and respect at the books of each other’s respective Scriptures.

This statue, reflective of the Jewish tradition of partnered Torah-study (havrutah), speaks of the new type of relationship that Nostra Aetate both encouraged and has helped to make possible. Today, many Jews and Christians are mutually enriched by their study of the other’s religious traditions and texts, and this statue points to those new possibilities for friendship and learning in each other’s company.

• Joshua Koffman: Sculpture Website

Chavrutah means "studying partners"

A Paradigm Shift

Toward Constructive Shalom Theology

Philip A. Cunningham, Seeking Shalom: The Journey to Right Relationship between Catholics and Jews, Michigan and Cambridge: Wm.B. Eerdmans, 2015.

About the cover art. One of the most transformative texts of the Second Vatican Council was its 1965 declaration on the relationship of the Catholic Church to non-Christian religions, known by its opening Latin words as Nostra Aetate ("In Our Time"). It repudiated centuries of Christian claims that Jews were blind enemies of God whose spiritual life was obsolete. This comptemptuous teaching had been depicted on many medieval churches by the female figures of Church (Ecclesia) and Synagogue (Synagoga), the former crowned and victorious, the latter defeated and blindfolded, her crown fallen at her feet. Nostra Aetate repudiated such images. It declared that Jews are beloved by an ever-faithful God whose promises are irrevocable, and called for dialogue between Christians and Jews.

To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Nostra Aetate, Saint Joseph's University commissioned an original sculpture by Joshua Koffman entitled Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time. Today Synagoga and Ecclesia are able to learn about God from each other. As Pope Francis has written: "Dialogue and friendship with the children of Israel are part of the life of Jesus' disciples. There exists a complementarity between the Church and the Jewish people that allows us to help one another mine the richess of God's word" (Evangelii Gaudium, 2013). The cover photo shows the full-size clay version of the sculpture, which will be cast in bronze.

Charting an Unprecedented Journey. The Hebrew word shalom [... and its] many connotations [... are] particularly relevant to the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. Usually translated into English as peace, shalom in its fuller meaning actually denotes prosperity, well-being, and a sense of being whole and healthy. It involves being in right relationship with one's own community and with others. Shalom is also sometimes understood as the outcome of walking trough life with God.

Clearly, Christianity has not been in "right relationship" with Judaism throughout most of the two millennia of its existence. As Cardinal Edward Cassidy has concisely summarized:

Given this tragic assessment, one ponders to what extent the church's lack of shalom with Judaism has impeded its continuation of the mission of Jesus to prepare the world for the Reign of God. As Cardinal Walter Casper has poignantly written, "[C]utting itself from its Jewish roots from centuries weakened the church, a weakness that became evident in the altogether too feeble resistance against the [Nazi] persecution of Jews" (Cunningham, Christ Jesus and the Jewish People Today: New Explorations of Theological Inerrelationships, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011, xiv). To put it in another way, if over the centuries the Christian community has not been in right relationship with its Jewish roots, its Jewish neighbors, and indeed in some ways with its Jewish Lord, then how successful coulld it be in being an agent of shalom in the world?

The Catholic Church, together with most Christian denominations it has now renounced its past contempt for Judaism, as replaced, obsolete, or outmoded. It seeks to cultivate shalom with those now recognized to also be covenantal partners with God. Such shalom brings both external "right relationship" with the Jewish people and internal "right relationship" between the church's own Jewish heritage and its Christian self-definition. This wholeness seems essential if either Jews or Christians are to fulfill their covenanting responsabilities befor God toward the rest of humanity (pp xi-xii).

Cunningham's book explores the fifty past years of Christian-Jewish relation in terms of the new Catholic-Jewish interplay inspired by Nostra Aetate in 1965. The author considers the Church's attitude toward Jews and Judaism, including "constructive theology" and "an unprecedented opportunity for mutual enrichment and growth" (p. 256).

"Christian communities have embarked on a process of reforming inherited negative theological attitudes toward Jews and Judaism." Yet, "Given the longevity and pervasiveness of supersessionism in Christian teaching, this is an unpalleled and difficult process. It touches on all aspects of Christian faith including Christology, ecclesiology, soteriology, ethics, and liturgy" (p. 235). "It will require years of dedicated perseverance, not only because of the inhereted zero-sum* binaries of the past, but because we are finding our way along new and unexplored paths of mutuality" (p. 247).

* Zero-sum. Of, relating to, or being a situation (as a game or relationship) in which a gain for one side entails a corresponding loss for the other side.

Zero-sum is a situation in game theory in which one person’s gain is equivalent to another’s loss, so the net change in wealth or benefit is zero. A zero-sum game may have as few as two players, or millions of participants. In the financial markets, options and futures are examples of zero-sum games, excluding transaction costs. For every person who gains on a contract, there is a counter-party who loses. Win-Lose Binary. Win-Lose Interplay.

The bronze work, by noted Philadelphia artist Joshua Koffman, was installed on Sept. 25 in front of the Chapel of St. Joseph on the campus, commemorating the 50th anniversary of Nostra Aetate, the Vatican II document that transformed the relationship between the Catholic and Jewish people. The sculpture is part of the celebration of Nostra Aetate that attempts to display in art the quantum leap made since the promulgation of the document in reversing erroneous views of Jews and Judaism. Nostra Aetate sought to repudiate centuries of Christian claims that Jews were blind enemies of God because of their rejection of Jesus as the Messiah, and that their spiritual life was superseded by Christianity.

The statue at St. Joseph’s University reflects the teaching of the Catholic Church today as enunciated clearly by the present and past four popes. "Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time" depicts synagogue and church as both proud crowned women, living in covenant with God side by side, and learning from one another’s sacred texts and traditions, discussing their distinctive experiences of the Holy One. According to the university’s director of the Jewish-Catholic Institute, Philip Cunningham, the sculpture brings to life the words of Pope Francis: "Dialogue and friendship with the Jewish people are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. There exists between us a rich complementarily that allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another mine the riches of God’s Word" (Joseph D. Wallace, Synagogue and Ecclesia in Our Time, Catholic Star Herald, 1 October 2015).

In some depictions of this allegorical pair, we see a triumphant Ecclesia standing erect next to the bowed, blindfolded figure of the defeated yet dignified Synagoga (e.g., the thirteenth-century stone figures in the cathedrals of Strasbourg, Freiburg, Bamberg, Magdeburg, Reims, and Notre Dame [Paris]). Though the church has triumphed over synagogue, the latter is a tragic rather than sinister figure--a woman conquered, with her crown fallen, staff broken, and Torah dropping to the ground. ...

Other representations of Synagoga, particularly in the Late Middle Ages, present a more contemptible figure. For example, in a fifteenth-century portrayal of the crucifixion, Ecclesia holds a chalice to receive the blood from the pierced heart of Jesus, whereas Synagoga turns away from him, in the clasp of a devil who rides atop her neck and blinds her to the Christ by covering her eyes. The association with the devil evokes a malevolent Synagoga. ... Many [Medieval Christians] would have viewed the figures of Synagoga and Ecclesia, and thereby absorbed a dangerous lesson: Judaism no longer has reason to exist (Mary C. Boys, Has God Only One Blessing? - Judaism as a Source of Christian Self-Understanding, Paulist Press, 2000, 31-35).

Contrast this long-lived derogatory Christian attitude toward Judaism with these recent words of Pope Francis:

We hold the Jewish people in special regard because their covenant with God has never been revoked, for “the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable” (Rom 11:29). ... Dialogue and friendship with the children of Israel are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. The friendship which has grown between us makes us bitterly and sincerely regret the terrible persecutions which they have endured, and continue to endure, especially those that have involved Christians. God continues to work among the people of the Old Covenant and to bring forth treasures of wisdom which flow from their encounter with his word. For this reason, the Church also is enriched when she receives the values of Judaism (Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, 2014, 247-249).

Clearly Catholic attitudes have changed. A new relationship of respect has replaced the previous one of disdain. The turning point was the Second Vatican Council declaration, Nostra Aetate, issued on October 28, 1965.

The statue being prepared for Saint Joseph's University to mark the declaration's 50th anniversary will reinterpret the medieval motif of Synagoga and Ecclesia to reflect the teaching of the Catholic Church today. "Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time" will depict Synaogue and Church as both proud crowned women, living in covenant with God side by side, and learning from one another’s sacred texts and traditions about their distinctive experiences of the Holy One.

3. Sculpting a New Tradition: From Adversaries to Two Peoples in Covenant to Study Partners, SJU, April-July 2015

In Medieval Europe, the feminine figures of victorious Church (Ecclesia) and vanquished Synagogue (Synagoga) adorned dozens of cathedrals and churches. A famous depiction at the Cathedral of Strasbourg (ca. 1230) shows regal Church wearing a crown and bearing a cross-topped staff of authority and the chalice of the Eucharist. To the right, Synagogue is slumped and blindfolded, her crown has fallen to her feet, her staff is broken, and a tattered scroll of the Torah seems about to fall from her hand. Ill. Strasbourg

The figures also were regularly portrayed on either side of the crucified Jesus. Here in an early 15th century German Bible history book, Church collects the precious blood of Jesus into her chalice. Synagogue's vision is blocked by a demon on her head, who also casts off her crown.

When Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned King of Italy at the Cathedral of Milan on May 26, 1805, he ordered that work to complete its façade should begin at once. Seven years later, the traditional images of Synagogue and Church were transformed into somewhat secularized figures to show the legal equality of all religions in the Napoleonic state. Church is the Lady of Liberty of Enlightenment-era political thought, while Synagogue displays the universal philosophy of the Ten Commandments. Ill. Milan statues

In the first decades of the 20th century, the American artist John Singer Sargent reprised the medieval images of Synagogue and Church in paintings for the Boston Public Library. As in the older portrayals, she has lost her crown, her staff is broken, and her eyes are blindfolded. Although she retained some dignity in many medieval depictions, here she is thoroughly desolate. Such demeaning images contradict Catholic teaching since the Second Vatican Council's 1965 declaration Nostra Aetate. Ill. John Singer Sargent, Synagogue

For her book, Has God Only One Blessing? Judaism as a Source of Christian Self-Understanding (Paulist Press, 2000), Mary C. Boys commissioned Paula Mary Turnbull, a member of her religious community, to prepare small brass statues of Synagoga and Ecclesia as both in covenant with God. This idea of reimagining the negative medieval motif to reflect Catholic teaching since Nostra Aetate inspired the SJU sculpture to mark the declaration's 50th anniversary: "Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time." Ill. Paula Turnbull statuettes

With this basic premise, a number of artists were invited to submit concept sketches. One of Joshua Koffman's earliest clay drafts appealingly showed Church and Synagogue as comfortable being with and interacting with each other.

This interactive dynamic recalled the words of Pope Benedict XVI in 2011: "After centuries of antagonism, we now see it as our task to bring these two ways of rereading the biblical texts—the Christian way and the Jewish way—into dialogue with one another, if we are to understand God's will and his word aright." This led to the concept of portraying Synagogue and Church as sharing their respective sacred texts with each other, crudely suggested by inserting clip art texts to show them learning together.

Joshua Koffman took this basic concept and significantly developed it in another rough clay sketch. Besides having them holding their sacred texts, he added simple crowns to both figures, using that medieval symbol to indicate that both Synagogue and Church experience covenantal life with God.

In the final clay sketch before doing drapery studies for the Artist's Model, Joshua Koffman refined the Torah scroll and Christian Bible and how they are grasped. The image of Synagogue and Church reading together evokes the traditional Jewish chavruta method of studying the Talmud in pairs.

After doing drapery studies with live models, the larger Artist's Model is completed. The Torah scroll and Christian Bible are more substantial and are held in complementary ways. As Pope Francis has written: "God continues to work among the people of the Old Covenant and to bring forth treasures of wisdom which flow from their encounter with his word. For this reason ... there exists as well a rich complementarity [between us] which allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another to mine the riches of God’s word" [Evangelii Gaudium, 249].

4. Murray Watson, ICCJ concludes Annual Meeting in Rome, CCJR, 1.7.2015

(ROME) In a historic gathering in the Vatican on June 30, Pope Francis welcomed more than 250 Jewish and Christian leaders from the International Council of Christians and Jews. The Pope met with them to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the ground-breaking Vatican II declaration “Nostra Aetate,” which opened up new horizons in the Catholic Church’s approach to interfaith relations. [...]

The new statue of Ecclesia and Synagoga (Church and Synagogue) has been commissioned by Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia to honour the Nostra Aetate anniversary.

In contrast to the many portrayals of Ecclesia and Synagoga found in medieval cathedrals and manuscripts (which generally portrayed Ecclesia as triumphant, and Synagoga as defeated), this modern work of art depicts the two figures as equal in dignity and beauty, looking with curiosity and respect at the books of each other’s respective Scriptures.

This statue, reflective of the Jewish tradition of partnered Torah-study (havrutah), speaks of the new type of relationship that Nostra Aetate both encouraged and has helped to make possible. Today, many Jews and Christians are mutually enriched by their study of the other’s religious traditions and texts, and this statue points to those new possibilities for friendship and learning in each other’s company.

|

| "My representational work begins with the human. It is heavily influenced by tradition, serves a function, and speaks to a timeless audience. I first create the compositions in clay, mold them, and then cast them in bronze" Joshua Koffman All images reproduced with the sculptor's permission. |

Chavrutah means "studying partners"

A Paradigm Shift

From medieval darkness to contemporary light, Joshua Koffman's Contribution to Interfaith Dialogue | Cambio de paradigma. De la oscuridad medieval a la luz contemporánea: una contribución al diálogo interreligioso. | De l'obscurité de Strasbourg à la lumière de la Pennsylvanie.

Toward Constructive Shalom Theology

Philip A. Cunningham, Seeking Shalom: The Journey to Right Relationship between Catholics and Jews, Michigan and Cambridge: Wm.B. Eerdmans, 2015.

About the cover art. One of the most transformative texts of the Second Vatican Council was its 1965 declaration on the relationship of the Catholic Church to non-Christian religions, known by its opening Latin words as Nostra Aetate ("In Our Time"). It repudiated centuries of Christian claims that Jews were blind enemies of God whose spiritual life was obsolete. This comptemptuous teaching had been depicted on many medieval churches by the female figures of Church (Ecclesia) and Synagogue (Synagoga), the former crowned and victorious, the latter defeated and blindfolded, her crown fallen at her feet. Nostra Aetate repudiated such images. It declared that Jews are beloved by an ever-faithful God whose promises are irrevocable, and called for dialogue between Christians and Jews.

To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Nostra Aetate, Saint Joseph's University commissioned an original sculpture by Joshua Koffman entitled Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time. Today Synagoga and Ecclesia are able to learn about God from each other. As Pope Francis has written: "Dialogue and friendship with the children of Israel are part of the life of Jesus' disciples. There exists a complementarity between the Church and the Jewish people that allows us to help one another mine the richess of God's word" (Evangelii Gaudium, 2013). The cover photo shows the full-size clay version of the sculpture, which will be cast in bronze.

Charting an Unprecedented Journey. The Hebrew word shalom [... and its] many connotations [... are] particularly relevant to the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. Usually translated into English as peace, shalom in its fuller meaning actually denotes prosperity, well-being, and a sense of being whole and healthy. It involves being in right relationship with one's own community and with others. Shalom is also sometimes understood as the outcome of walking trough life with God.

Clearly, Christianity has not been in "right relationship" with Judaism throughout most of the two millennia of its existence. As Cardinal Edward Cassidy has concisely summarized:

There can be no denial of the fact that from the time of the Emperor Constantine on, Jews were isolated and discriminated in the Christian world. There were expulsions and forced conversions. Literature propagated stereotypes, preaching accused the Jews of every age of deicide; the ghetto which came into being in 1555 with a papal bull became in Nazi Germany the antechamber of the extermination... The Church can justly be accused of not showing to the Jewish people down through the centuries that love which its founder, Jesus Christ, made the fundamental principle of his teaching ("Reflections: The Vatican Statemen on the Shoah," Origins 28/2, 28 may 1998, 3).

Given this tragic assessment, one ponders to what extent the church's lack of shalom with Judaism has impeded its continuation of the mission of Jesus to prepare the world for the Reign of God. As Cardinal Walter Casper has poignantly written, "[C]utting itself from its Jewish roots from centuries weakened the church, a weakness that became evident in the altogether too feeble resistance against the [Nazi] persecution of Jews" (Cunningham, Christ Jesus and the Jewish People Today: New Explorations of Theological Inerrelationships, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011, xiv). To put it in another way, if over the centuries the Christian community has not been in right relationship with its Jewish roots, its Jewish neighbors, and indeed in some ways with its Jewish Lord, then how successful coulld it be in being an agent of shalom in the world?

The Catholic Church, together with most Christian denominations it has now renounced its past contempt for Judaism, as replaced, obsolete, or outmoded. It seeks to cultivate shalom with those now recognized to also be covenantal partners with God. Such shalom brings both external "right relationship" with the Jewish people and internal "right relationship" between the church's own Jewish heritage and its Christian self-definition. This wholeness seems essential if either Jews or Christians are to fulfill their covenanting responsabilities befor God toward the rest of humanity (pp xi-xii).

Cunningham's book explores the fifty past years of Christian-Jewish relation in terms of the new Catholic-Jewish interplay inspired by Nostra Aetate in 1965. The author considers the Church's attitude toward Jews and Judaism, including "constructive theology" and "an unprecedented opportunity for mutual enrichment and growth" (p. 256).

"Christian communities have embarked on a process of reforming inherited negative theological attitudes toward Jews and Judaism." Yet, "Given the longevity and pervasiveness of supersessionism in Christian teaching, this is an unpalleled and difficult process. It touches on all aspects of Christian faith including Christology, ecclesiology, soteriology, ethics, and liturgy" (p. 235). "It will require years of dedicated perseverance, not only because of the inhereted zero-sum* binaries of the past, but because we are finding our way along new and unexplored paths of mutuality" (p. 247).

* Zero-sum. Of, relating to, or being a situation (as a game or relationship) in which a gain for one side entails a corresponding loss for the other side.

Zero-sum is a situation in game theory in which one person’s gain is equivalent to another’s loss, so the net change in wealth or benefit is zero. A zero-sum game may have as few as two players, or millions of participants. In the financial markets, options and futures are examples of zero-sum games, excluding transaction costs. For every person who gains on a contract, there is a counter-party who loses. Win-Lose Binary. Win-Lose Interplay.

The bronze work, by noted Philadelphia artist Joshua Koffman, was installed on Sept. 25 in front of the Chapel of St. Joseph on the campus, commemorating the 50th anniversary of Nostra Aetate, the Vatican II document that transformed the relationship between the Catholic and Jewish people. The sculpture is part of the celebration of Nostra Aetate that attempts to display in art the quantum leap made since the promulgation of the document in reversing erroneous views of Jews and Judaism. Nostra Aetate sought to repudiate centuries of Christian claims that Jews were blind enemies of God because of their rejection of Jesus as the Messiah, and that their spiritual life was superseded by Christianity.

The statue at St. Joseph’s University reflects the teaching of the Catholic Church today as enunciated clearly by the present and past four popes. "Synagoga and Ecclesia in Our Time" depicts synagogue and church as both proud crowned women, living in covenant with God side by side, and learning from one another’s sacred texts and traditions, discussing their distinctive experiences of the Holy One. According to the university’s director of the Jewish-Catholic Institute, Philip Cunningham, the sculpture brings to life the words of Pope Francis: "Dialogue and friendship with the Jewish people are part of the life of Jesus’ disciples. There exists between us a rich complementarily that allows us to read the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures together and to help one another mine the riches of God’s Word" (Joseph D. Wallace, Synagogue and Ecclesia in Our Time, Catholic Star Herald, 1 October 2015).

• Resources

• Has God Only One Blessing?

• Interfaith Dialogue in Our Time

• Arte y Diálogo Interreligioso

• Ayer y Hoy

• Album Ecclesia et Synagoga

• Wikimedia Pic

• Vesalius Rio Program

Great article on Joshua Koffman's sculpture and what it represents.

ReplyDeleteGorgeous and moving.

ReplyDeleteAn informative piece on the relevance and importance of the sculpture created by Joshua Koffman that was honored by the Pope at St. Joseph's University in Philadelphia on September 27, 2015.

ReplyDeleteIn one bold and eternal image Joshua has reinterpreted the ancient story of Synagoga and Ecclesia from one defining difference and highlighting religious hierarchy to a more contemporary dialogue of shared experience and similarity. In our world right now where religions are struggling violently to understand one another this work of art stands as the power of possibility.

This is why art matters.

Realmente una lección.

ReplyDeleteMerci de me faire découvrir cela. C'est superbe à tous points de vue.

ReplyDeleteStriking sculpture in Philadelphia. I think this is remarkably a propos of your research: Dotty Brown, "Pope Francis Makes Surprise Stop To Bless Sculpture Symbolizing Catholic Unity With Jews," Forward, 28/9/2015, http://forward.com/news/321629/pope-francis-makes-surprise-stop-to-bless-sculpture-symbolizing-catholic-an/

ReplyDeleteIndeed, thanks a lot.

ReplyDeleteOjalá que el mensaje del Papa Francisco llegue a quienes debe llegar. La gente tarda añares en cambiar las ideas.

ReplyDelete